Earlier, I’ve written about how high-rise residential buildings have higher construction costs, land costs, floorplan efficiency, and maintenance costs than low-rise buildings. But leave it to some supertall skyscraper architects to make the ecological case for low-rise multifamily, with the book Residensity. The Chicago-based architects ran analyses on nine different arrangements for 2,000 residential units, from detached suburban houses to 215-story skyscrapers, and found that the optimal type was the humble courtyard apartment.

This housing type, typical of medium-density lakefront neighborhoods in Chicago (see Moss Design), is a low-rise version of a European perimeter block. Multiple apartment entrances are arrayed around a courtyard, each reaching up to six flats (one on either side, for three floors). The deep courtyard evolved (see Ultra Local Geography) from the practice of putting apartment entrances along both streets on corner lots, and a clever response to Chicago’s relatively deep lots. They’re not quite single stair point-access blocks, though: each apartment technically also accesses a second stair — an exterior fire escape, usually built as a sociable rear porch. (21st-century building codes do not count this as a legal egress.) Courtyard apartments also allow for shallower, more usable interior floor plans; unlike mid-century “garden apartments” they structure open space into urbane settings.

The Smith/Gill team found that courtyard apartments had:

- lowest embodied CO2 for buildings and infrastructure combined

- lowest operating energy demand

- 94% land savings vs. suburban houses

- density that enables energy-efficient transportation modes

In some sense, this shouldn’t be surprising: the high construction costs and operating costs for high-rises are, in large part, paying for large quantities of carbon-intensive materials and energy to go into their construction and operation. The high operating energy demand reflects the large building surface areas that tall buildings have, as well as inefficient floor plans with extensive interior spaces. In a skyscraper, everyone on floor 150 has to travel indoors past everyone on floors 1-149 to get to anything outside the building; in a courtyard apartment building, most of that travel is outdoors.

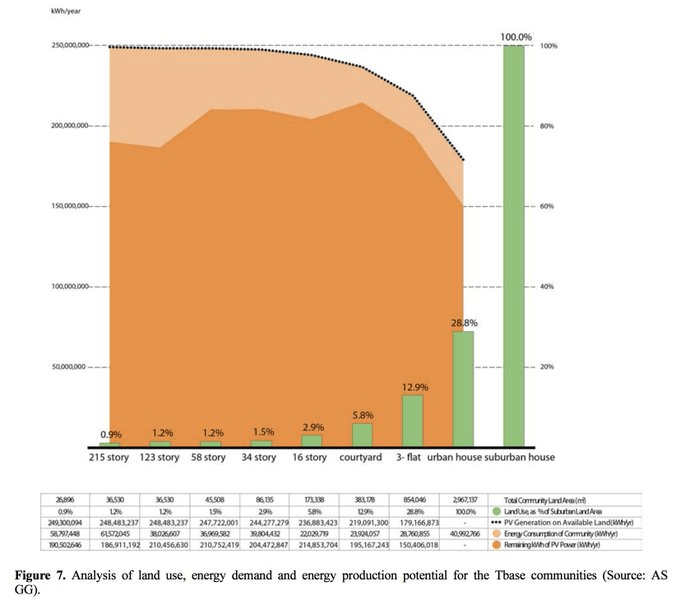

Most striking to me is the density effect: high-rises aren’t incredibly more land efficient (shown by the green bars) than low-rise multifamily. For the same population, three-story apartments use 87.1% less land than suburban houses, courtyard apartments use 94.2% less, and high-rises uses 97-99% less land. Thus, low-rise apartments offer 90-97% of the land savings that high-rises do.

This paper also didn’t consider CO2 emissions from transportation: almost 1/3 of all US CO2. (The US accounts for 45% of the whole world’s transport CO2!) The greatest potential for transport CO2 reductions is to raise low densities to moderate, not high to higher: “the relationship between density and emissions is nonlinear,” says Grist about a PNAS journal article by Conor Gately — echoing Newman & Kenworthy’s finding from 1999.