- Site news! I’ve put up a searchable archive of my Tweets at https://paytonchung.github.io, principally for my own reference. I’m probably most often at Bluesky, though I also maintain a Mastodon account.

- Three recent posts I’ve written for Greater Greater Washington:

- Get the crowd back together: Office conversions won’t be enough to rebuild downtowns’ population density. Just converting existing office buildings to residences won’t be enough to stop the “urban doom loop,” because apartment buildings contain many fewer people than similarly sized office buildings do. Fewer people means fewer services, which after all, serve people. Maintaining those services with a population of residents will require much higher population densities – and many new buildings – rather than just conversions.

- The 1% solution: Regulating new construction is a really slow way to change an entire city.

Regulating today’s new construction is a very slow way to address tomorrow’s social needs, since almost all of tomorrow’s houses and buildings were built…yesterday. Even the most radical changes to newly built homes won’t change much about America’s housing situation until decades from now. (Unless, of course, a lot more buildings start getting built.) - What’s the deal with single-tenant retail buildings? Despite thoughtful GGWash articles asking for something else, single-story retail buildings stubbornly hold on in many prominent locations, and sometimes even multiply. Surprisingly, a freestanding chain store can often be the highest-value use of a piece of land. That’s because commercial real estate investors in the U.S. offer favorable terms to owners and tenants of these ubiquitous retail boxes, making them more lucrative than other buildings.

- Speaking of things I wrote about in GGWash (ten years ago), economists Michael Eriksen and Anthony Orlando discovered the “hidden height limit” (aka construction cost discontinuity) that keeps buildings below eight stories.

Tag Archives: housing

High rises’ high cost, part 4: ecological cost, and the superiority of low-rise courtyard apartments

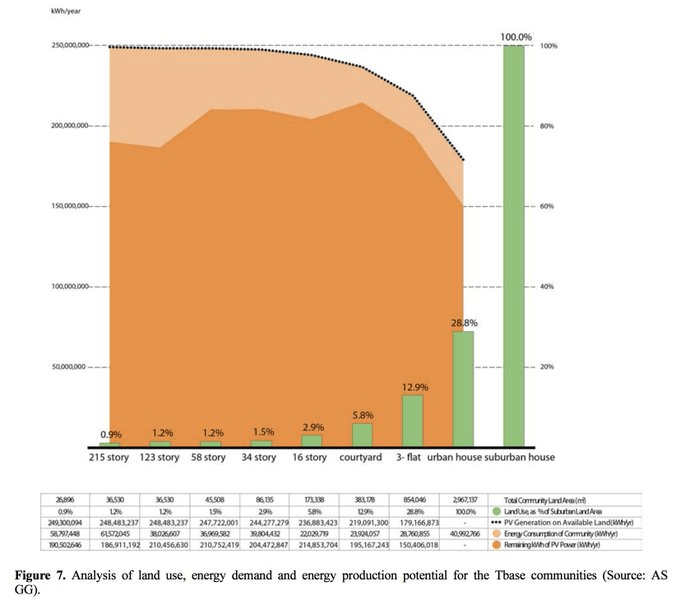

Earlier, I’ve written about how high-rise residential buildings have higher construction costs, land costs, floorplan efficiency, and maintenance costs than low-rise buildings. But leave it to some supertall skyscraper architects to make the ecological case for low-rise multifamily, with the book Residensity. The Chicago-based architects ran analyses on nine different arrangements for 2,000 residential units, from detached suburban houses to 215-story skyscrapers, and found that the optimal type was the humble courtyard apartment.

This housing type, typical of medium-density lakefront neighborhoods in Chicago (see Moss Design), is a low-rise version of a European perimeter block. Multiple apartment entrances are arrayed around a courtyard, each reaching up to six flats (one on either side, for three floors). The deep courtyard evolved (see Ultra Local Geography) from the practice of putting apartment entrances along both streets on corner lots, and a clever response to Chicago’s relatively deep lots. They’re not quite single stair point-access blocks, though: each apartment technically also accesses a second stair — an exterior fire escape, usually built as a sociable rear porch. (21st-century building codes do not count this as a legal egress.) Courtyard apartments also allow for shallower, more usable interior floor plans; unlike mid-century “garden apartments” they structure open space into urbane settings.

The Smith/Gill team found that courtyard apartments had:

- lowest embodied CO2 for buildings and infrastructure combined

- lowest operating energy demand

- 94% land savings vs. suburban houses

- density that enables energy-efficient transportation modes

In some sense, this shouldn’t be surprising: the high construction costs and operating costs for high-rises are, in large part, paying for large quantities of carbon-intensive materials and energy to go into their construction and operation. The high operating energy demand reflects the large building surface areas that tall buildings have, as well as inefficient floor plans with extensive interior spaces. In a skyscraper, everyone on floor 150 has to travel indoors past everyone on floors 1-149 to get to anything outside the building; in a courtyard apartment building, most of that travel is outdoors.

Most striking to me is the density effect: high-rises aren’t incredibly more land efficient (shown by the green bars) than low-rise multifamily. For the same population, three-story apartments use 87.1% less land than suburban houses, courtyard apartments use 94.2% less, and high-rises uses 97-99% less land. Thus, low-rise apartments offer 90-97% of the land savings that high-rises do.

This paper also didn’t consider CO2 emissions from transportation: almost 1/3 of all US CO2. (The US accounts for 45% of the whole world’s transport CO2!) The greatest potential for transport CO2 reductions is to raise low densities to moderate, not high to higher: “the relationship between density and emissions is nonlinear,” says Grist about a PNAS journal article by Conor Gately — echoing Newman & Kenworthy’s finding from 1999.

Two Japanese new-house ads, explained

Here’s a Google-translated ad for new houses for sale in suburban Hiroshima; just this one small advertisement for new houses required a lot of research and explaining to make sense!

- Housing is indeed inexpensive: the prices are around ¥30M (=3,130 x ¥10,000), or about US$200K at the current, extremely favorable, exchange rates.

- Mortgage terms are unbelievable. Note the monthly payment of ¥60K, or US$400 given a 50-year (!) mortgage at 0.45% (!). No wonder the carry trade is so huge!

- As a result, these new houses are broadly affordable; the monthly payment is just 13.6% of the 2019 median household income in Hiroshima prefecture (Japanese household income/expense survey link).

- Then again, housing is less than 10% of household expenditures in Japan. About 43% of Japanese households are unmortgaged homeowners, which appears to be a fairly typical percentage among OECD countries.

- Contrast that with American consumers, who spend US$2,120 per month on housing – more than Japanese consumers spend on everything in a typical month.

- The houses are small, but space-efficient and land-efficient. They’re ~1100 square feet, but fit 3-4 bedrooms, and sit on lots about as large – small even by “small lot” US standards. I’m guessing that zoning limits the site to a 1.0 floor-to-area ratio, which would be typical of an urban neighborhood in the US.

- At lower right is a tiny subdivision plot plan. Small “mini-kaihatsu” subdivisions like this (<1000 m2, or ~11K sq ft) are exempt from site-permit review, reducing the “soft costs” of building housing. Besides, semi-private residential alleys have long been where workers have lived in East Asian cities, whether Beijing’s hutongs or Osaka’s nagaya.

- The street widths would be considered unconscionably narrow by US standards that frequently require 50′ rights-of-way. Yet at 5-6m (16-19.6′), they comfortably exceed the 4m (13′) national minimum; this is meant for car access, after all.

- The location that matters most: “8 minute walk to train station” is in the upper right corner (cropped out in this view). The “two car parking” probably assumes two tiny kei cars, and is more likely enough for one normal car plus some bikes. After all, you can’t register a car without having an off-street parking space.

Building and zoning codes reference link: www.iibh.org/kijun/japan.htm

Brookings Institute overview www.brookings.edu/articles/japan-rental-housing-markets/

English blog on Japanese housing: catforehead.com/

If those are the prices for suburbia, how about infill? Here’s an ad for new high-rise condos in the downtown area of Yokosuka, a seaside southern suburb of Yokohama that’s home to a large US Navy base. It’s half an hour to Yokohama by train and one hour to southern Tokyo, and one-bedroom units begin at ¥27M, or US$177K today.

This ad was for a Keikyu condo, near a Keikyu station, and seen on a Keikyu train. Land development is how American streetcar systems made their fortunes, and it’s still a legitimate business model across Asia today.

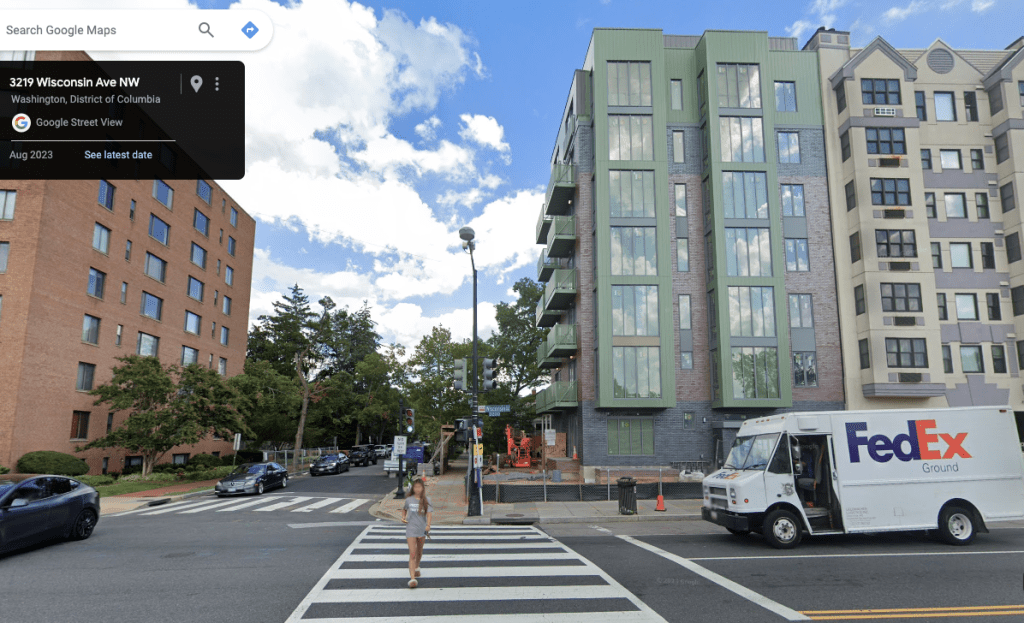

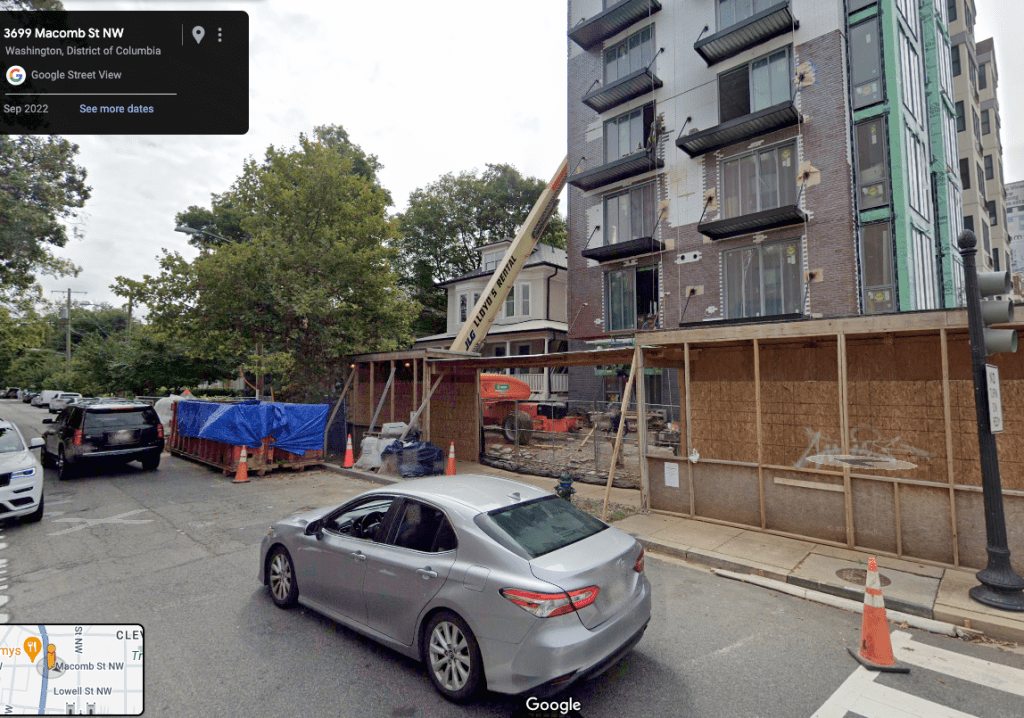

Where redevelopment is too costly, create infill sites through house-moving

This house on Wisconsin Ave. NW was demolished by greedy high-rise developers — no, wait, it was merely moved around the corner to face Macomb St. The high-rise is actual infill, in that it fills in what had been a square of grass. Keeping the house (which might have been part of a bargain with the neighborhood) can help to recoup most of the land acquisition cost.

Infill, rather than demolition, was pretty typical of how “missing middle housing” was originally built in its early 20th-century, pre-zoning heyday. It’s also how middle housing development generally pencils in the present day: “the best way to make an infill project work is to avoid demolition.”

Even though houses in locations like Upper NW DC are expensive, houses’ yard space is some of the lowest-valued land in cities. Moving a house on its lot is a way to buy just the yard while leaving the use value of the house intact.

I had hoped to take a similar approach with my Redgrove project by building new houses just within the backyard and calling the entire site a “cottage court.” Alas, I couldn’t get zoning permission to call it a cottage court. Raleigh allows “flag lots” (a site that wraps around an existing house) but only for one or two units, not 10. The only legal way to get more than a few units (indeed, up to 41 units!) was with only townhouses or multifamily on site, and so the original house will be demolished soon. Inflexible planning rules (minimum lot sizes, frontage requirements) don’t allow this sort of mix-and-match development.

(Edit 2025. Glad to see my strategy and experience validated in a Portland city report about middle housing: “cottage clusters… can sometimes preserve existing structures that are well positioned on the original lot to allow building on the remainder of the site… a challenge [arises] because preservation necessarily means the builder has less site area, flexibility, and fewer new structures… These realities mean sites where preservation is an option (or financial necessity) aren’t as workable as they could be.”)

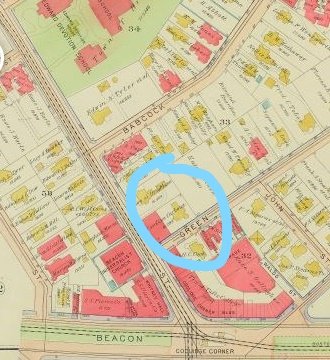

A century-old example is the Coolidge Corner section of Brookline, Massachusetts, where my grandparents once bought a triple-decker and where John F. Kennedy grew up. The NPS website for the JFK house includes this Sanborn insurance map slider, which shows how Coolidge Corner’s building stock changed between 1907 and 1919 — including both the Kennedy’s house and my grandfather’s triple-decker.

The maps shows that flats (shown on the fire insurance maps in red, as they were built out of fireproof brick) were usually built on vacant, but already subdivided, house lots. Sometimes, a wooden house (shown in yellow) would be moved on its lot to make room for flats–e.g., the two circled houses at the corner of Harvard and Green Streets were rotated away from Harvard St. to make room for shops on the same lot. A ~1919 photo shows Jack and Joe Kennedy Jr. standing amidst a half-built suburban subdivision. Few houses were demolished entirely to build just flats — though some were for larger buildings, like the mixed-use complex in the obtuse corner.

People like Rose Kennedy, who moved into a new-ish wooden house in Coolidge Corner in 1914, did not approve. In 1973, just after my family arrived, she called the area “built up now… congested and drab” (pg. 33). Keep in mind that Joseph Kennedy Sr. moved there as a bank president. Single lots and detached houses in Coolidge Corner in the 1910s were already a luxury, perhaps because restrictive covenants required a minimum house value.

Despite those covenants, this pre-zoning suburb was demographically mixed—because nuclear-family SFH-owners like the Kennedys were the exception, while extended families & renters were the norm. The 1920 Census found the Kennedys’ block was 68% renters and had 47 unrelated boarders! Roomers and live-in servants were surprisingly common in many urban and suburban neighborhoods into the early 20th century, until early zoning advocates forced them out. In that sense, my grandfather bringing his multigenerational family (and renters) to the area wasn’t anything new, even in a rich suburb like Brookline. Also, every neighborhood has always been changing forever and always will, the end.