Crowdfunding built this little store.

A few years ago, during the darkest days of the financial crisis, I was the finance director for the Dill Pickle Food Co-op, launching the crowdfunding campaign that ultimately raised enough capital to open what’s now a thriving local institution. I’ve also worked in commercial real estate finance, closely examined how economics and ownership structures affect gentrification, and deeply interested in how to use capital to build authentic places. So I was obviously very interested in what Fundrise was starting here in Washington, D.C., and ultimately chose to invest in their latest project on H St. Their approach has been extensively covered in the media, for instance by Emily Badger in Atlantic Cities and David Lepeska in Next City.

Jonathan O’Connell in the Post offers a different critique: financial advisors who reviewed the offering’s legal documents had strong reservations about its merit as an investment.

My reading of the offering docs concurs with the advisers: The developers, and the large-dollar investors, get preferred classes of stock (and hence voting control, first dibs on returns, and priority in the event of liquidation), plus a guaranteed return via management fees. “The crowd” gets Class C common stock. We small shareholders, in return for our small contributions, ultimately receive no vested control over the project, stand last in line for returns, and stand first in line to be wiped out in bankruptcy.

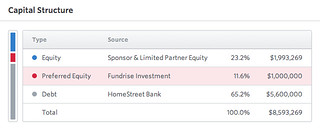

[Update May 2015: As of this time, the majority of Fundrise offerings are currently for “preferred equity.” First, Fundrise itself purchases an equity stake with a stated return, paid either during the investment term or at the end of the term. Then, investors purchase debt backed by that stake — accounting and tax compliance are much easier for debt than for equity. Their offerings also now include a clearer illustration of the capital stack.

The short of it: as is typical with preferred equity, Fundrise investors receive no control, stand second in line for returns (with promised, but not guaranteed, returns), and stand second in line in bankruptcy (with no secured guarantees). In the capital stack illustration, control rests at the top end, risk is highest at the top end, and returns are paid first from the bottom end — debt gets paid first, then preferred equity, then equity gets what’s left over.]

Matt Yglesias in Slate points out that Fundrise can involve its “small-business silent partners” under an SEC regulation “whose main use in the recent past was financing Broadway shows” — and, indeed, I’m reminded of how little control the little-old-lady investors have over Max Bialystock in “The Producers.”

So now that expectations have been suitably lowered, what’s in it for both the developers and the community? Why did I still think this was an experiment worthy of watching from the inside?

A. Cheaper, slower money.

Think about a typical real estate situation: a homeowner with a house. When that house is sold, people get paid in this chain:

1. First mortgage

2. Second mortgage (in commercial real estate, this is a “mezzanine loan”)

3. Homeowner (“equity”)

Risk increases down the chain, but so do rewards and control.

What Class C shares do is to create an equity class with higher risk, lower returns, and no control. This equity isn’t sufficient to forego debt altogether — there’s still a mortgage on the property — but it’s enough to displace high-rate mezzanine financing, and therefore move the preferred equity investors up the chain. Since these loans are generally the highest-cost financing that a developer receives, and usually written with very brief loan terms, they create the greatest incentive to quickly lease the space to a “credit” (i.e., boring) tenant. Common stock is more patient: in fact, we Class C shareholders are so patient that we’re investing without any expectation about when, or even if, we get our money back. In short, it’s similar to a co-op’s membership equity: maybe your money will be there at the end, and maybe you’ll get paid along the way if we choose to declare a dividend, but we don’t guarantee anything and it’s probably easier to think about your equity as a donation.

The reduced cost and reduced “velocity” of capital reduces the developers’ incentive to quickly flip the property, and certainly eases longer-term thinking about the investment. Real estate has an intrinsic susceptibility to wide value swings: construction introduces an inherent delay that prevents supply from quickly aligning with demand, resulting in severe market imbalances throughout the business cycle. Patient capital that can wait out these swings is best poised to profit from true placemaking — hence the family-controlled real estate dynasties that control so much of central New York, London, and Hong Kong.

Yet in this instance, the managers might not take full advantage of their capital’s patience. The offering documents clearly state that the developer plans to sell or refinance the property after a few years, and may well cash out the Class C shareholders at that time. While this may provide Class C shareholders with a conveniently timed liquidity event, five years isn’t exactly a long-term investment in the community.

B. Participation and trust.

Perhaps a bigger — if unquantifiable — benefit for developers is that crowdfunding quite literally demonstrates community buy-in. As Yglesias writes, “A huge network of small-time, commercial real-estate shareholders could provide a much-needed counterweight to the plague of NIMBYs strangling America’s cities.”

Fundrise knows this power, which is why they’ve just floated a project on Florida Avenue that they don’t yet have control over — and even though the terms of the RFP appear to give the edge to another, conventionally financed project team. By letting residents “vote with their dollars,” Fundrise thinks that they can level the playing field between the big, bad developer and the little community. They also benefit from a broad shift in whom we trust: Americans have declining trust in institutions (government, developers, banks) and a technology-mediated concomitant increase in trust between individuals (e.g., Kiva for loans, Lyft for hitchhiking). Instead of just complaining, a well-capitalized community can act on the mantra to “be the change you wish to see in the world.”

In the context of gentrifying Washington, D.C., this strategy might not engender unlimited goodwill: the crowd looks too much like both Matt Yglesias and me: quite heavy on the “myopic little twits” of local lore: young, petit-bourgeois, tech-savvy guys with vanishingly little street cred. In a uniformly gentrified neighborhood like Cleveland Park or Brooklyn Heights or Uptown Minneapolis, “one dollar, one vote” might not be such a big deal, and community finance can definitely tap into the “silent majority” that might desire reinvestment vs. stasis. However, those locales are hardly underserved by conventional finance strategies. Instead, Fundrise is operating in more stratified urban neighborhoods, where banks are still wary of lending against more-speculative land values — and where even a modest capital requirement prevents the venture from truly reaching across the economic divide.

Even the completely community-based Dill Pickle (and other coops like it) encountered resistance by those who viewed it as an agent of gentrification. Not enough resistance to derail the project, to be sure, but plenty of grumbles nonetheless.

C. An opening for even better investment vehicles.

These two reasons — and the idea that, in terms of diversifying my portfolio exposure to real estate, H St. NE is as good a location as any for a 3-5 year speculative play — were reason enough for me to decide that Fundrise was worth a gander. I doubt that it’s really going to take off in a big way: even if its practice is standardized and the market becomes more liquid, crowdfunding still seems like a lot of legwork to raise a relatively small sum, especially given the amount of capital necessary for large-scale urban real estate development.

Fundrise is certainly a great idea, but the lack of community control limits its ability to establish trust in the community development enterprise. Yet it’s an important part of a broader conversation that’s just beginning around using crowdfunding innovations to improve communities. We can try many other tools — some new, some tried-and-true — to give communities greater control and input over their character and future. Cooperative businesses, like the one I founded, are growing all across America, and they play a key role in affordably housing thousands of Washingtonians (including myself). Financial co-ops, better known as credit unions, are quickly growing in the USA — and in some states, they have branched out past basic consumer lending and increasingly lend to or buy equity stakes in small businesses, even at the venture stage. Canadian banking law gives credit unions much wider scope, which allows them to do more for their communities: Vancouver’s Vancity isn’t just a carbon-neutral, living-wage, triple-bottom-line company, it also has $16 billion in deposits (enough to make it the largest or second-largest bank in the context of a similarly sized metro area like Denver or Pittsburgh). Over in Toronto, the Centre for Social Innovation has raised millions of dollars for community-development and clean energy projects through its community bonds. Since they’re bonds, not equity, they can be issued without prospectuses, and can even be held through RRSPs (Canada’s version of an IRA).

Edited to reflect that all Fundrise equity is “pari passu,” and has equal claim in the event of default.