Ever wonder how “parking” came to mean two very diametrically opposed things — dead pavement and living green space? Historian Kirk Savage offers an explanation in his book Monument Wars:

In the nineteenth century, to park meant to plant a tree or spread a patch of turf or flowers–to create a little patch of parkland. In Washington, the Parking Commission was a group of respected horticulturalists who supervised street-tree planting. On the city’s wide streets, parking places typically referred to strips of grass, flowers, or trees plated alongside the pavement, or in the larger squares or circles. These strips of parking* not only cooled the streets but made them more manageable by reducing their great width and the amount of paving they required. By the turn of the century, such parking areas were sometimes used to hold horse-drawn carriages on special occasions; these were temporary intrusions that did not threaten the parkland itself. When automobiles started to overrun cities in the early twentieth century, parking areas were given over to car storage and the word began to refer to the cars themselves rather than the trees and grass they were replacing. The new meaning of the word intertwined with the old in strange ways. In 1924, for example, the park in front of Centre Market, “one of the few spots of green along Pennsylvania Avenue,” was converted into a “parking space” for cars over the opposition of the city’s “superintendent of trees and parkings,” who lamented that “the oil and gasoline from the parked automobiles will quickly kill whatever trees are left standing.” In early 1927, the District commissioners, acting on citizen complaints, appointed a committee to try to stop “the practice of parking automobiles on the grass-sown parkings between sidewalks and curbs.” At the same time, however, city officials were also beginning to cut down street trees throughout downtown Washington and widen pavements to make room for automobile traffic and parking (in the new sense). Literally and metaphorically, the new parking conquered the old.

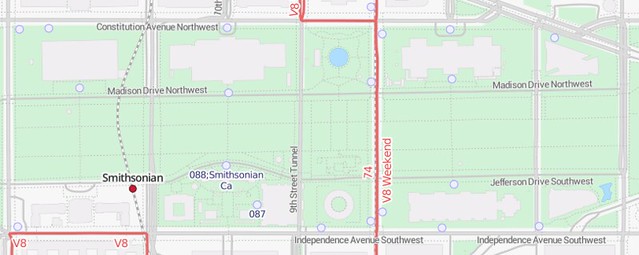

Another fun fact from the book: the axis of the National Mall was tilted about 1.5° south so that the Capitol and Washington Monument appear to line up. Since the Monument was built off-axis, it doesn’t line up anything in the L’Enfant Plan, and that’s still subtly visible in some views. Now that I know this, I can’t un-see its crookedness on any map of the city.

* In Chicago, the local dialect persists in calling areas like the planting zone between sidewalk and street “the parkway.”