[DC Council Committee of the Whole testimony]

Thank you for providing the opportunity to testify regarding Bill 26-227, the One Front Door Act of 2025. My name is Payton Chung; I am a Ward 6 resident, an infill residential developer, and a longtime contributor to, and now acting chair of, Greater Greater Washington Commons. I have written twice in GGWash about how single-stair buildings can improve overall life safety and about how single-stair buildings are already found throughout DC’s historic neighborhoods.

First, single-stair apartment reforms could actually improve fire safety rather than compromise it. Fire deaths have declined dramatically—by 90% over the past century and 60% in recent decades—and that is primarily because new buildings are far safer than older buildings, as referenced in previous testimony from Seva Rodnyansky and Eric Mayl.

Building codes, like all regulations, necessarily balance public safety with cost. Today, homebuyers in our high-cost region often turn to existing buildings, or to residential code structures such as townhouses. These lack many of the fire protections found in the more stringent commercial code, such as sprinklers and fire-rated walls and doors. The One Front Door Act offers a path forward to moderate the cost of safer commercial-code structures on smaller infill sites.

Current double-egress rules force most apartments above three stories into double-loaded corridor layouts with units facing interior hallways and windows on only one side, preventing natural ventilation. Single-stair reforms would enable better-ventilated apartments with windows on multiple sides, particularly beneficial for family-friendly units, while maintaining modern fire safety standards through sprinklers and other protections.

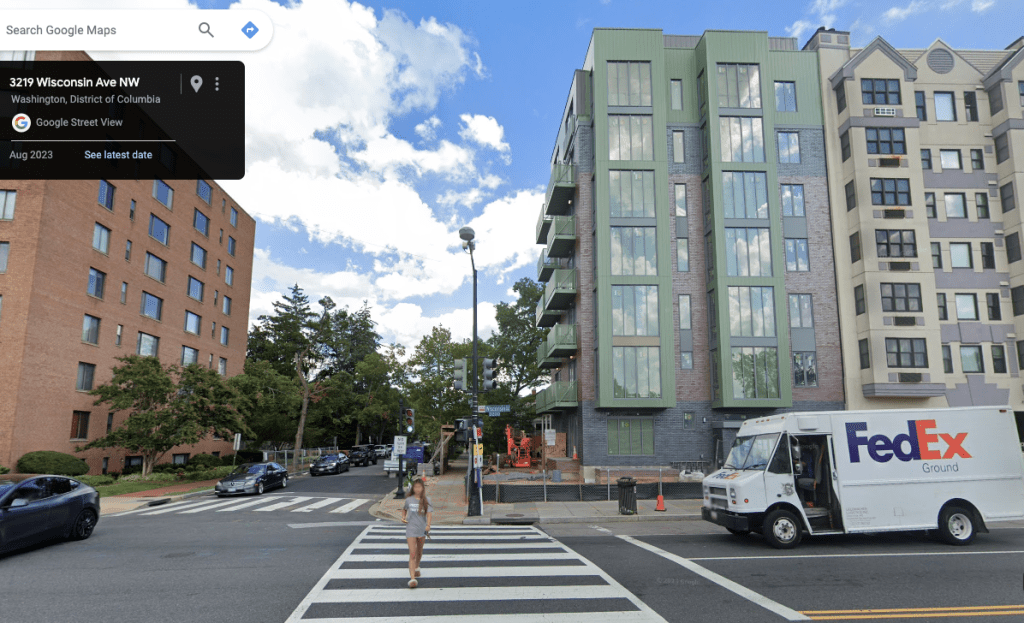

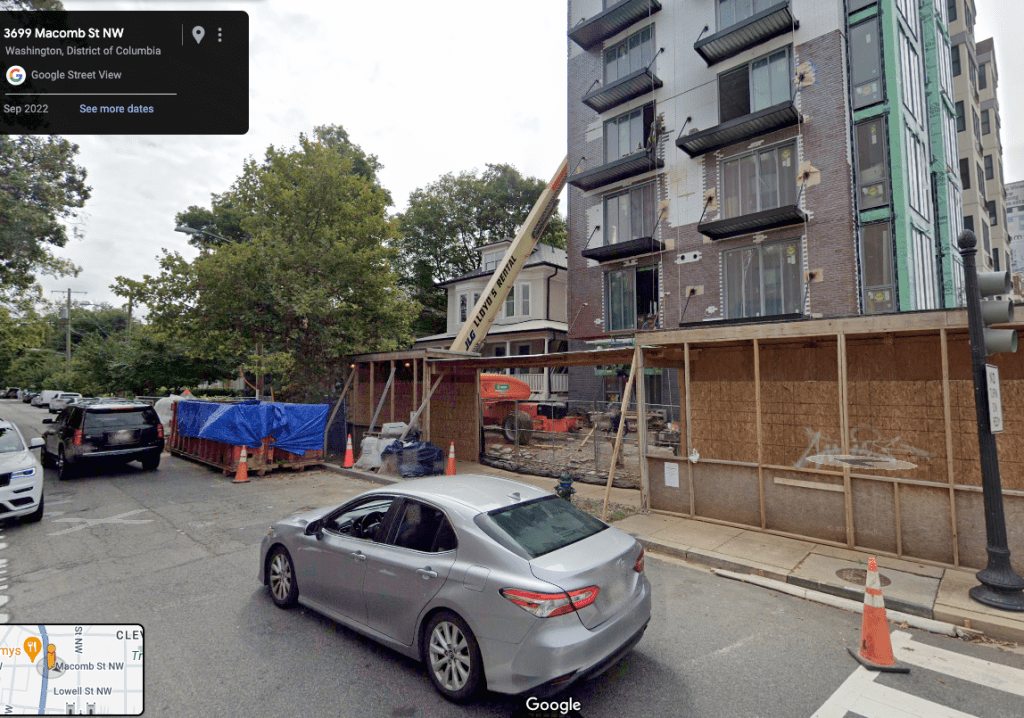

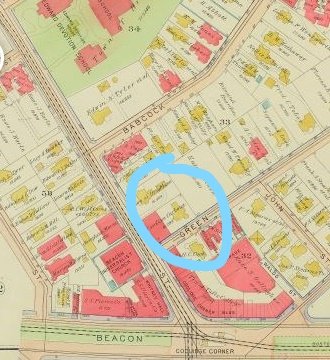

Second, I’ve written about how single-stair buildings have served Washingtonians well over the past century. Historical examples include the Gladstone Cooperative in Ward 1, which fits on a lot the width of three rowhouses, showing that single-stair designs enable efficient middle-class housing on narrow parcels.

McLean Gardens in Ward 3, built during World War II to house war workers, received a temporary Fire Escape Act waiver allowing four-story wood-framed buildings with single exit staircases. The development features narrow buildings wrapped around landscaped courtyards with 31 entrances, each serving just a few apartments.

Harbour Square in Ward 6 uses “scissor stairs”—combining two stairs in the space of one—enabling slender tower designs with cross-ventilated units. Unlike today’s double-loaded corridor buildings, these historical examples offered diverse unit types including family-sized three-bedroom apartments, with single-stair layouts allowing windows on multiple sides and units facing the outdoors rather than hallways.