Two presentations given at YIMBYtown 2025:

- Expanding Infill Affordable Homeownership Pathways

2. Who killed Missing Middle Housing – and how?

Two presentations given at YIMBYtown 2025:

2. Who killed Missing Middle Housing – and how?

Presentation given at the Smart Growth America Equity Summit, March 2025.

Here’s a Google-translated ad for new houses for sale in suburban Hiroshima; just this one small advertisement for new houses required a lot of research and explaining to make sense!

Building and zoning codes reference link: www.iibh.org/kijun/japan.htm

Brookings Institute overview www.brookings.edu/articles/japan-rental-housing-markets/

English blog on Japanese housing: catforehead.com/

If those are the prices for suburbia, how about infill? Here’s an ad for new high-rise condos in the downtown area of Yokosuka, a seaside southern suburb of Yokohama that’s home to a large US Navy base. It’s half an hour to Yokohama by train and one hour to southern Tokyo, and one-bedroom units begin at ¥27M, or US$177K today.

This ad was for a Keikyu condo, near a Keikyu station, and seen on a Keikyu train. Land development is how American streetcar systems made their fortunes, and it’s still a legitimate business model across Asia today.

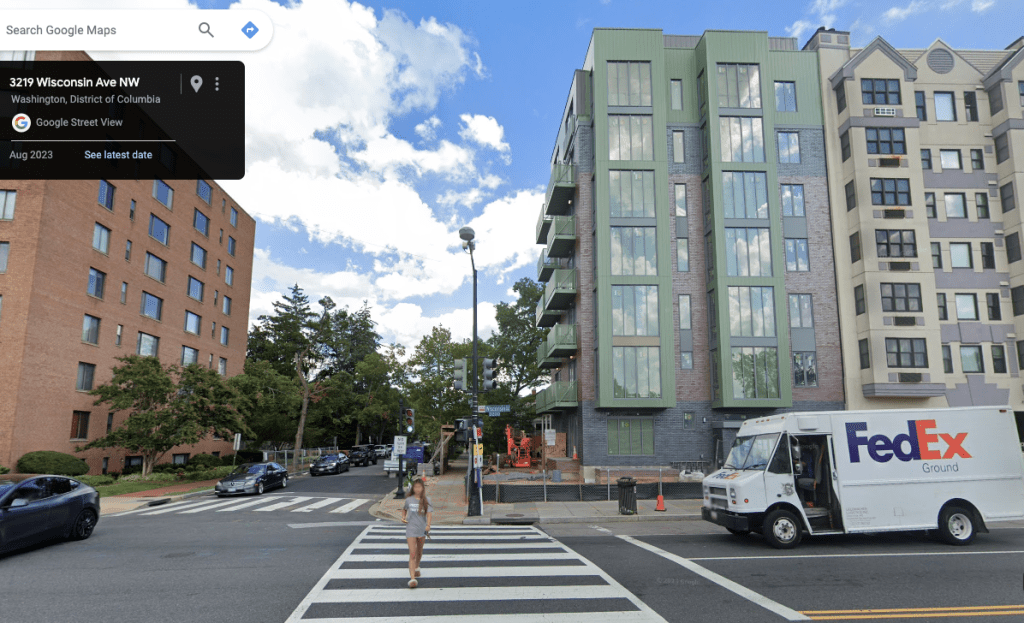

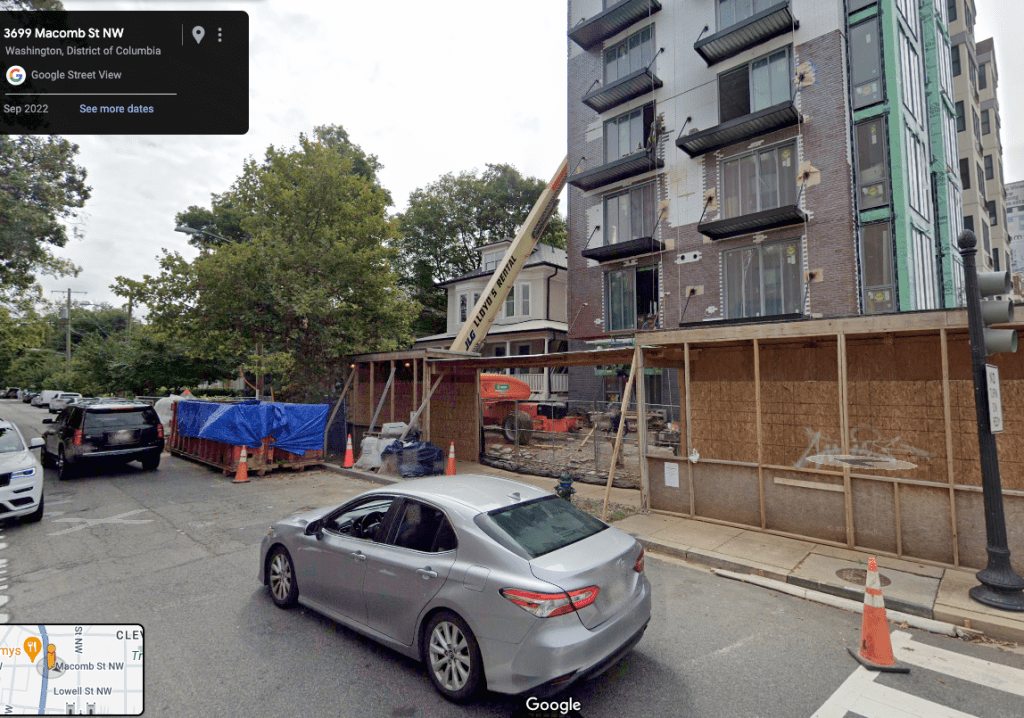

This house on Wisconsin Ave. NW was demolished by greedy high-rise developers — no, wait, it was merely moved around the corner to face Macomb St. The high-rise is actual infill, in that it fills in what had been a square of grass. Keeping the house (which might have been part of a bargain with the neighborhood) can help to recoup most of the land acquisition cost.

Infill, rather than demolition, was pretty typical of how “missing middle housing” was originally built in its early 20th-century, pre-zoning heyday. It’s also how middle housing development generally pencils in the present day: “the best way to make an infill project work is to avoid demolition.”

Even though houses in locations like Upper NW DC are expensive, houses’ yard space is some of the lowest-valued land in cities. Moving a house on its lot is a way to buy just the yard while leaving the use value of the house intact.

I had hoped to take a similar approach with my Redgrove project by building new houses just within the backyard and calling the entire site a “cottage court.” Alas, I couldn’t get zoning permission to call it a cottage court. Raleigh allows “flag lots” (a site that wraps around an existing house) but only for one or two units, not 10. The only legal way to get more than a few units (indeed, up to 41 units!) was with only townhouses or multifamily on site, and so the original house will be demolished soon. Inflexible planning rules (minimum lot sizes, frontage requirements) don’t allow this sort of mix-and-match development.

(Edit 2025. Glad to see my strategy and experience validated in a Portland city report about middle housing: “cottage clusters… can sometimes preserve existing structures that are well positioned on the original lot to allow building on the remainder of the site… a challenge [arises] because preservation necessarily means the builder has less site area, flexibility, and fewer new structures… These realities mean sites where preservation is an option (or financial necessity) aren’t as workable as they could be.”)

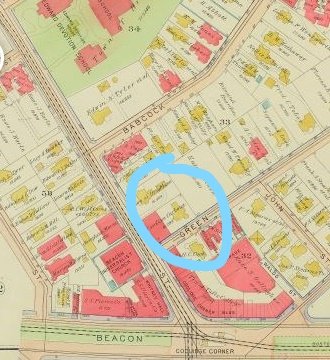

A century-old example is the Coolidge Corner section of Brookline, Massachusetts, where my grandparents once bought a triple-decker and where John F. Kennedy grew up. The NPS website for the JFK house includes this Sanborn insurance map slider, which shows how Coolidge Corner’s building stock changed between 1907 and 1919 — including both the Kennedy’s house and my grandfather’s triple-decker.

The maps shows that flats (shown on the fire insurance maps in red, as they were built out of fireproof brick) were usually built on vacant, but already subdivided, house lots. Sometimes, a wooden house (shown in yellow) would be moved on its lot to make room for flats–e.g., the two circled houses at the corner of Harvard and Green Streets were rotated away from Harvard St. to make room for shops on the same lot. A ~1919 photo shows Jack and Joe Kennedy Jr. standing amidst a half-built suburban subdivision. Few houses were demolished entirely to build just flats — though some were for larger buildings, like the mixed-use complex in the obtuse corner.

People like Rose Kennedy, who moved into a new-ish wooden house in Coolidge Corner in 1914, did not approve. In 1973, just after my family arrived, she called the area “built up now… congested and drab” (pg. 33). Keep in mind that Joseph Kennedy Sr. moved there as a bank president. Single lots and detached houses in Coolidge Corner in the 1910s were already a luxury, perhaps because restrictive covenants required a minimum house value.

Despite those covenants, this pre-zoning suburb was demographically mixed—because nuclear-family SFH-owners like the Kennedys were the exception, while extended families & renters were the norm. The 1920 Census found the Kennedys’ block was 68% renters and had 47 unrelated boarders! Roomers and live-in servants were surprisingly common in many urban and suburban neighborhoods into the early 20th century, until early zoning advocates forced them out. In that sense, my grandfather bringing his multigenerational family (and renters) to the area wasn’t anything new, even in a rich suburb like Brookline. Also, every neighborhood has always been changing forever and always will, the end.

(Sent to Raleigh City Council)

I urge you to support Z-92-22, the New Bern Avenue TOD overlay mapping.

As a student at Enloe High School in 1996 (photograph at right), I gained some unpopularity for suggesting that students ought not to complain about parking and press for a costly parking garage, because other options existed — i.e., the city bus. 30 years later, a faster and better city bus could be an option for more residents, but only if City Council lets people live nearby.

In short, this is a vote on whether or not Raleigh transit succeeds. Transit succeeds when it has a mass of people to transport, and without TOD this BRT will fail, just like the many other transit plans that Raleigh has drawn up over my lifetime.

In a 2016 referendum, 262,634 Wake County voters said yes to this specific Bus Rapid Transit line, obliging the city of Raleigh to create a mass transit system — not just to deliver the transit project, but also to ensure its success by making it useful for a mass of people. The federal government, which is funding half of this project, is closely evaluating whether federal taxpayers’ monies are well-spent in places whose zoning laws truly welcome transit. The federal government has made it amply clear that it has learned the lessons of places like Los Angeles and Denver (as amply reported in NPR’s series “Ghost Train”) which wasted billions in federal funds on building empty new transit lines in locations that lacked a mass of residents and businesses.

Raleigh’s failure to federal transit funding in the past was entirely because our land use plans have not supported transit. This has been the story since I was a child, and now I’m middle-aged. You finally have a golden chance to make transit work in Raleigh by passing Z-92-22.

Most of the fearmongering around this rezoning has centered on displacement. TOD overlay zoning is the only Inclusionary Zoning tool that Raleigh has at its disposal, and therefore voting FOR this rezoning is a vote to bring inclusionary zoning here. This rezoning will focus more development on under-used commercial land and large-lot houses, reducing the pressure for flippers who are already displacing residents from nearby neighborhoods.

As Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez says, “the reason why people are on the streets isn’t just some elusive housing or market phenomenon. It’s because we’ve chosen not to build.” The voters of the city of Raleigh have risen to the challenge by approving funding for affordable housing, but now we need places to put it – and Z-92-22 does just that. The city has invested mightily to prepare by buying affordable housing sites within this overlay district.

Zoning for housing is the progressive thing to do. Data For Progress analyzed every 2020 presidential platform and found that “every major Democratic candidate for president endorsed an explicitly pro-housing platform, calling for an end to exclusionary zoning,” while many Republican leaders have attacked Missing Middle zoning reforms using thinly veiled racist language. In his final act in Congress, the Triangle’s own David Price passed the Yes In My Back Yard Act grant program as part of the 2023 federal budget.

A “no” vote on Z-92-22 is not a vote for some magical, supernatural, and completely nonexistent perfection that might exist in the future. Instead, a “no” vote on Z-92-22 is a vote to perpetuate an unjust, unsustainable status quo of cars and sprawl: for bulldozing thousands more acres in Wendell, more deadly car crashes on the Beltline, more carbon pollution to drown our precious beaches, to perpetuate the exclusionary covenants that banned both people of color and renters from Longview Gardens.

There has been enough study and delay; the Equitable Transit-Oriented Development Guidebook recommending this rezoning was issued in July 2020, almost three years ago. Now is the time for action.

I thank you for your attention. I look forward to further working with the City of Raleigh to advance our shared vision of a greater Raleigh.

I remember being excited about having a greenway between downtown Cary and the subdivision where I grew up (and beyond to Lake Johnson, NC State University, and Downtown Raleigh) back when I first saw it in a town parks plan in the library — in the 1980s, when I was a child. My parents went to some public meeting in the 1990s that they said was discouraging, and for decades I have regretted that I wasn’t there to speak up for the project then.

So here I am, several decades later, to say that this should be completed posthaste. And speaking as a planner, public engagement should include the voices of people who will benefit, far beyond those abutting the project boundary and far beyond today.

(The above is an email I sent to Cary’s parks planner upon finding out that the trail project is being actively studied again. If only it had been done, decades of development alongside it like Fenton could’ve tied into an existing transportation facility — but instead, no, instead the future trail is fronted by parking lots.)

Presentations given at CNU 31 on June 2, 2023

1. Payton Chung, Westover Green – introduction (Google Slides)

2. Monte Anderson, Options Real Estate

3. Susana Dancy, Rockwood Development

4. Abbey Oklak, Kimco Realty

Presentation given at CNU 31: Open Innovations on June 2, 2023. PDF embedded below, or Google Slides version.

(Italicized sections were cut entirely from the delivered testimony for brevity.)

Thank you for the opportunity to speak. My name is Payton Chung. After grad school for planning at Virginia Tech in Arlington, I am now a developer of Missing Middle scaled housing. Because that job does not yet exist around here, I mostly work in Raleigh, NC, a prime destination for people who have been priced out of northern Virginia. I can attest that Raleigh’s Missing Middle text changes have made it possible for me to offer smaller, lower-priced houses than the large new houses built across the street just before the text changes. Many of those arriving in Raleigh have been priced out of places like Arlington, which has better infrastructure than Raleigh — much better transit, no water shortages, a regionwide trail network, less crowded schools — but which lacks sufficient housing infrastructure.

The “tall or sprawl” dichotomy of Arlington’s “bulls-eye approach” to planning relies almost entirely on two uniquely high-cost housing types: land-intensive detached houses and capital-intensive high-rise apartments. As a result, it necessarily results in high housing costs. Missing Middle Housing offers a middle ground: less land than detached houses and less materials and labor than high-rises. Yet Missing Middle Housing production, like production of anything else, best achieves lower costs once it achieves economies of scale. It can only reach its full potential for lower costs if it becomes widespread and well-practiced.

Not only does this call for removing artificial zoning limitations, but it also requires related changes to building codes, financing practices, and construction practices. That means allowing more units, in more locations, and not rationing it with a countywide cap. Redevelopment is already an inherently slow process, since it’s limited by land availability. Only 3/10ths of 1% of Arlington’s single family houses are listed for sale today. Progress towards the county’s equity, affordability, or sustainability goals should not be further limited.

EHO will not solve the affordable housing crisis, but it will make existing subsidy dollars and programs go much further. For instance, Virginia Housing offers subsidized loans to first-time homebuyers up to a cap of $665,000. A house at that price is roughly affordable to the median Arlington household. Right now, there are zero new construction houses available in Arlington to meet that budget. Some older houses are available, but with either maintenance needs or condo fees that would sink many first-time homebuyers. However, there are 108 new homes available under that cap in equally land-constrained, equally highly regulated DC and Alexandria — and 98% are in “missing middle” sized buildings that are basically illegal to build in Arlington today. Instead, new houses in almost all of Arlington are available only for households earning more than the President of the United States — top-3% incomes in America.

The EHO text attempts to incentivize 4-6 flat buildings, but building codes and lending practices continue to favor fee-simple townhouses. I suggest further study to adapt building codes to enable flats, review townhouses’ specific urban design challenges, require public access easements so that driveways contribute to the street network, and allowing townhouse accessory dwelling units– “English basements” are an established pattern for attainable housing in this region.

And last, a quick response to complaints about infrastructure sufficiency. Infrastructure is continually repaired and replaced, for example through Arlington’s $4.4 billion Capital Improvement Program — including almost $1 billion just in water infrastructure. We’ve known since the federal government’s 1974 “Costs of Sprawl” report that expanding existing infrastructure in existing urbanized areas is more cost effective than building it new in rural areas.

Take rail transit, for example: restricting growth here means that Arlington pays WMATA extra to run trains with excess capacity here, while Virginia spends billions to expand rail service for Arlington commuters’ hour or two-hour trips to Ashburn and Ashland. Instead, Arlington should welcome more of those commuters to live here and take the trains built decades ago, when doing so was much cheaper. At a time when new houses are being sold to Arlington commuters in Caroline County, 70 miles down I-95, we need to be cognizant that while infrastructure in Arlington might not be perfect, it’s much better than infrastructure elsewhere.

It’s especially puzzling to hear complaints about strained infrastructure come from neighborhoods where the population has shrunk, rather than grown. Even as Arlington’s population grew by 15% since 2010, CPHD estimates that the population in Old Glebe declined by 13.6%. When Arlington’s low-density neighborhoods were built, life expectancy was still in the 60s; now a typical Arlingtonian lives to 85. That’s terrific news, but it means that Arlington needs more housing units even for exactly the same population — much less a growing one.

I commend the Commission and County for the progress made to date. This zoning change may seem momentous, but even the dry and bitter pill of zoning reform is not a magic pill. It can merely reshape changes that are already occurring to neighborhoods, and hopefully in a way that shifts rather than reinforces the unjust, unsustainable status quo.

Thanks to Councilmember Allen for this opportunity to speak. I’m Payton Chung, LEED Accredited Professional in Neighborhood Development, and I have 20 years of experience in urban planning policy, notably in urban design and affordable housing.

Comprehensive planning is how a city adapts to an inevitable future. No plan, and indeed no action a city can take, can prevent that future from occurring.

One inevitable aspect of the future that deeply worries me, as one of the three billion humans living near sea level, is climate change. I previously testified that the updated comp plan does an adequate job of outlining several of the challenges and forward steps that DC will need to take over the next decade to forestall and adapt to the climate catastrophe. If left unchecked, many of Ward 6’s most vulnerable areas, for example the James Creek corridor along Delaware Ave SW, will be uninhabitable within my lifetime. I also testified earlier that the next iteration of the Comp Plan should address this existential threat to DC’s future as its foundation, not as one element among many.

I’d like to briefly touch upon the price of housing. Increased rents cause new buildings, not the other way around. Once rents surpass a level that can pay the surprisingly high underlying cost to build new houses, then new buildings will get built. Stopping new buildings might avoid offending some people’s aesthetic sensibilities, but does absolutely nothing to change the underlying demand for new housing. We can see this in the fact that rents have increased faster in Capitol Hill, with almost no new housing construction, than in Capitol Riverfront, which has lots of new housing construction.

I’m glad that the comp plan accepts that more houses are needed right here in Ward 6. Ward 6 residents enjoy many transportation choices, and so we produce far less carbon per capita than most Americans. The most effective contribution that neighborhoods like ours can make to the climate crisis is to let some more people in on our secret, and allow more neighbors to benefit from this fantastic location. To be clear, almost all of DC’s population growth results from babies that are born here, so growth is a matter of letting children stay here, not a matter of outsiders vs. insiders and us vs. them.

DC alone can’t change growing income and wealth inequality, or the fact that new houses are expensive to build – though it must continue to expand subsidies to help lower income residents access homes in high opportunity areas. But moderate- and middle-income residents could afford new construction on the private market, if only it were legal to build new homes everywhere, not just in a few tiny areas that I’ve called “instant neighborhoods,” and the comp plan calls Land Use Change Areas. This comp plan update begins to soften the distinction between Land Use Change Areas and Neighborhood Conservation Areas. That distinction has succeeded too well at comforting the District’s already comfortable single-family homeowners, sometimes overwhelming LUCAs with lots of change all at once, and pushing all new housing demand into high-rise apartments, which are the absolute most expensive kind of house to construct.

DC’s zoning makes it illegal to build all but the most expensive possible houses: detached palaces surrounded by huge yards in Ward 3, or high-rise studios surrounded by costly concrete and steel in Ward 6. Yet somehow, we act surprised that housing costs are out of reach. Allowing a broader variety of housing choices across the entire spectrum of housing types and neighborhoods, and particularly making it simpler to add new units in less costly low-rise apartments, will better balance the housing market and make sure that our housing dollars, whether private or public, go further.

As of 2015, the IBC now permits multi-story concrete podiums. At first, this was mostly of interest because it permitted even taller “double podium” apartment buildings, with up to eight stories framed mostly in wood.

This diagram (by Nadel, Inc. for Multifamily Executive) shows the effect between The Podium and The (Double) Podium: you can squeeze an additional floor in above grade, and because it’s concrete (heavy line) it can be used for residential, retail, or parking.

Yet using that magical concrete-framed second floor for residential (which could just as easily be wood-framed) seems like a bit of a missed opportunity. Instead, the second floor could be a mezzanine parking level for the wood-framed residential above — as was done in the mixed-use Grey House at River Oaks District pictured above, or in this mixed-use development on LA’s Olympic Blvd.

The real breakthrough possibility for the parking mezzanine isn’t atop retail, though: it’s atop yet more parking.

It just so happens that a 65-75′ wide module fits either a double-loaded apartment building or a double-loaded parking aisle. Therefore, a four-story building (three floors of Type V residential, one level of parking) can be stacked atop an existing aisle of parking — without diminishing the existing parking lot, and without excavating any parking.

It’s the suburban infill version of “have your cake and eat it, too”: keep your parking and add infill housing, too.

Developing these air-rights infill parcels used to require some pretty tremendous trade-offs. The first such projects that I saw were designed by Gary Reddick, a Portland architect who won a CNU Charter Award in 2004 for two such projects. Jury chair Ellen Dunham-Jones subsequently wrote about these in HDM:

In Seattle and Portland, where there are very good markets for residential development, Sienna convinced a variety of non-residential building owners to sell the air rights over their parking lots or roofs for housing. In Portland’s desirable and compact Northwest neighborhood, Sienna saw the parking lot of a specialized medical center as a potential housing site. After producing a pro forma, the firm approached the owners and showed that it could provide them with a covered, forty-three-space parking lot (with only three fewer spaces than before) and a million-dollar profit in exchange for stacking an additional layer of parking (with a separate entry) and two stories of condominiums. The built project, Northrup Commons, screens the parking with duplexes entered from the streets and adds two floors of apartments.

This turns out to be tough to replicate elsewhere. Because the residential comes with its own parking requirement, fully replacing the on-site parking requires adding parking somewhere else — either building a new parking lot elsewhere, or digging underground, at super-high cost ($11 million at one Seattle project). Most of the Sienna projects, including Northrup, used sloping sites (common in the Northwest) to tuck one parking level partially or fully underground.

Since the resulting buildings would block visibility and doesn’t result in an active ground-floor frontage, this particular infill seems best for infilling around Class B offices that currently sit adrift in a moat of parking — such as the above complex on Old Courthouse Road, at the southern fringe of Tysons Corner (image from Bing Maps). Or, many properties along this stretch of the infamous Executive Boulevard near White Flint (image from Google Earth):

* A rough assumption here is that each 1,000 sq. ft. apartment would have one parking space, which works out to about 3:1 residential:parking floor space. The ratio seems to work for the Houston example, which promises its residents the ability to park in-building rather than having to venture outdoors. Sufficient parking for rich Houstonians is probably enough for anyone.