Maybe for these rowhouses, since they’re in a “Land Use Change Area.” Photo by Mr. T in DC.

Metro’s recently publicized 2040 plan for a new downtown loop line elicited a lot of consternation by many city residents, wondering why the new subway line hewed so closely to the existing downtown. The short answer is: because they won’t need new subways. It ultimately comes down to cost and benefit: new subway construction is so expensive that it can only serve the highest-density neighborhoods. Instead of a plan to connect every rowhouse in the city to a subway, it’s a plan to maximize capacity to and through the regional core at a minimal cost.

As Matt Johnson wrote in a recent GGW post, “Metro’s studies found little need for a new subways outside of downtown based on the expected travel patterns in and density of those areas in 2040.” Ben Ross clarifies in a follow-up: “Why isn’t Metro planning more rail lines inside the Beltway? One big reason is that political pressure and federal regulations require it and other transit agencies to look only at current zoning and master plans… This forecast, in practice, is prepared by cobbling together the master plans adopted by local governments, which are not anyone’s best guess of the future, but mostly reflect the desires of locally dominant political forces.”

WMATA’s staff echo this on their PlanItMetro blog: “Many of you have said that we missed or have asked why we don’t have a line to . As part of this plan, we have analyzed almost every corridor or mode that you have identified.”

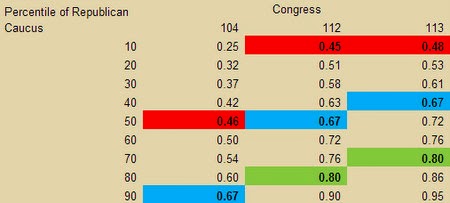

A recent Cal study by Erick Guerra and Robert Cervero examined the cost-effectiveness of various rail transit extensions vs. the population and employment density of the areas served, and determined a cut-off aggregate density of 100 persons (residents and jobs) per acre as a cut-off for high-cost heavy rail:

In this region, per research from Terry Holzheimer at Arlington Economic Development (full PDF), only downtown D.C. and a handful of high-rise suburban centers surpass that threshold:

Notably, though, the historic neighborhoods of Georgetown and Old Town — while surprisingly surpassing Edge Cities in intensity — fall well short of that density threshold. Laurence Aurbach calculated per-acre intensities for a few other historic neighborhoods, and of them only Dupont Circle [112.7] achieves downtown-level intensity, appropriate given that it’s chockablock with mid-rise office and hotel. Capitol Hill [44.8] and Logan Circle [57.1] also fall well short of 100 persons/acre.

The DC comprehensive plan gives precious little scope for other non-downtown areas within central DC to intensify much further. Nor do they seem to want intensification: DC neighbors will have a cow over one 6-story building one block from Metro. Contrast that to the 33-story apartment towers next to Metro in olde-timey Alexandria, 15-story office towers surrounding the Metro stations in mostly-rural Loudoun County, and heck, 40-story towers proposed along a Beverly Hills subway that’s at least ten years away. Those transit-supportive densities are impossible to build in the “neighborhood conservation areas” that comprise most of the District’s land area.

Meanwhile, the areas designated for “land use change” (in essence to be annexed to the mid-rise downtown) are NoMa and Capitol Riverfront. Connect those two neighborhoods to Union Station and Georgetown,* via bypasses of the Rosslyn and L’Enfant choke points, and add a few connecting points at the edges of downtown so that people can reach destinations like Union Station without going through Metro Center, and you’ve clearly defined WMATA’s proposed downtown loop subway.

Another instructive comparison to Paris might be in order: Washington, with its low density and low transit cost effectiveness, has 41 heavy rail stations and single-family rowhouses just one or two miles from the core, whereas Paris has flats stretching to the city limits, lower rail construction/operating costs, and almost 300 heavy rail stations within the city.

Of course, not all is lost, rowhouse neighborhoods! Note that light rail has much lower population density thresholds — and that DC has a plan for that.

* We can perhaps give Georgetown a pass, since the crowds of tourists visiting its shops don’t show up in either the resident or employee numbers.