Chicago’s zoning code has a built-in bias against smaller apartments – except in a few high-density zoning districts, which cover a vanishingly tiny slice of the city.

The zoning ordinance regulates building size and density in three ways: through floor area ratio (FAR), “minimum lot area per unit” (MLA, a backwards way of saying dwelling units per acre), and through various setback regulations. Yet these don’t follow a linear relationship at all; instead, the interaction between FAR maximums and MLA minimums encourages larger buildings with fewer apartments in lower-density districts, and more apartments per building in higher-density districts.

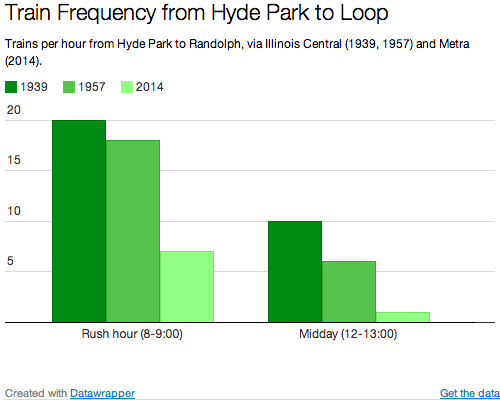

What this graph shows is: If I have a standard city lot in a given zoning district, and I build the biggest possible building with the most possible units, how large would those units be? The answer varies tremendously across the city, from a low of ~600 square feet in high-density districts like RM-6 and DR-7, to “impossible” in the lowest-density districts (note 1).

Most of the city’s neighborhoods, from the Bungalow Belt through the Zone of Two-Flats (mostly zoned RS-3) and into the Zone of Three-Flats (mostly RT-4), is zoned for the lowest-density (left-most) third of this graph. From RM-4.5 on down, the average apartment that can be built at the maximum density must be 1,250 square feet or larger (the size of a large two-bedroom apartment). Sure, you could build studio and one-bedroom apartments, but then you’d have to build huge three- and four-bedroom apartments, too.

Only for RM-5 and above, high-density zoning classifications pretty much only found in a narrow band along the lakefront, do the average apartment sizes permitted begin to dip into one-bedroom territory.

Someone who wishes to build new smaller apartments, like one-bedrooms or studios, in order to accommodate shrinking households can only do so in neighborhoods like Lakeview or Logan Square by either (a) under-building the FAR, at a considerable opportunity cost, or (b) getting rezoned to a denser category. Anyone who goes the latter route might as well build a lot bigger and higher, too.

Methodology notes:

- I assumed a standard 25′ x 125′ (3,125 sq. ft.) city lot. In RS-1 and RS-2, you cannot build on a lot that small, hence those values are excluded.

- The MLA chosen is the number specified for efficiency apartments, a distinction made in higher-density districts which would skew their figures down.

- “BCD” here refers to mixed-use zones that can be designated Business, Commercial, or Downtown depending on the use. What’s important for these purposes is the numeral in the zone name, which defines the density allowed. These zones all permit (and indeed, require) substantial amounts of commercial floor space, which counts against FAR but not MLA; for these zones, I assumed an apartment building with 0.5 FAR of commercial space, and the rest residential. This skews the figures upwards for downtown districts, where one would reasonably expect more than 0.5 FAR of commercial space.