“A diamond is forever, a suburban R-1 zone nearly so” – Jonathan Levine, “Zoned Out”

And what’s even more permanent than an R-1 zone? A condominium.

See those townhouses tucked among the trees? Hope you like them, ’cause they’re there, forever. (CC photo of Dearborn Park, Chicago, by Doug Nichols)

The saga of the Frontiers West condominium along 14th St. NW — as told by Lydia DePillis a few years ago — recently came up in conversation. A few years ago, multiple developers attempted to buy the entire complex, but ran up against an implacable foe: consensus. “Redeveloping any one of the parcels,” DePillis reports, “would require unanimous consent from the owners of all 54 units—so just one person could doom any deal.”

Frontiers had been built as public housing in 1977, an attempt to revitalize a neighborhood still deeply scarred by riots a decade earlier, and was sold off to tenants in the 1990s. (Jack Kemp introduced a Thatcher-esque scheme to sell public housing to tenants during the Bush 41 administration.)

Frontiers West’s unusual backstory created an unusually wide “rent gap” (the difference between value as-built and value as highest and best use) at that location. However, condominium ownership is over 50 years old in America, and thus the first stick-built condos are probably running up against their expected service lives. For those buildings, the economics of depreciating structures will soon run up against appreciating land values, and associations with structural problems (and in good locations) will have to face tough decisions. Says one condo owner outside Vancouver (probably the most condo’d city in North America), “We don’t have a system that allows people to understand what to do at the end of their unit’s life.”

It’s not necessarily impossible to buy every single owner out. MetroWest in Fairfax is being built on what was a low-density subdivision, where every owner consented to the sale. In a single-family situation, it should be possible in most cases to buy most of the parcels and leave a few “nail houses” outstanding.* Eminent domain, as at Atlantic Yards in Brooklyn, is also an option in situations where legal justification can be found.

Steven J. Smith found one recent example of a 30-unit condo — a singularly awful 1970s building in Chicago’s Lincoln Park — that had been re-assembled. (Maybe it helps that Illinois law requires only 75% of units to force an en-bloc sale.) But for other examples, he points overseas to Singapore and Japan — both even more urbanized than the USA, but also both societies where achieving political consensus is easier (their effective one-party rule being the prime example).

Singapore took Thatcher’s idea of council-flat ownership to an extreme, encouraging Singaporeans to purchase their public housing units with their social pension funds. (It’s also a clever way of locally recycling capital to fund their ambitious housing scheme.) Now that some of these buildings have become attractive redevelopment opportunities, the government has begun a “selective en-bloc redevelopment scheme” (or SERS, in the acronym-happy Singaporean government-speak) for scores of 1950s-1980s concrete-slab tower blocks, provided that 80% of owners consent. It helps that HDB flats are technically not owned, but instead are tied to 99-year leases; this gives HDB the authority to do things like impose anti-speculation rules to keep prices stable between the time redevelopment is announced and all individual contracts close.

Speaking of unique authority, this is one area where the greater legal flexibility granted to cooperatives, rather than condos, can come in handy. Whereas New York condominium law requires 80% approval for an en-bloc sale, its cooperative law only requires 2/3 consent to dissolve the corporation. For the particularly obstinate, District of Columbia law also permits cooperatives to kick out individual members through a simple majority vote.

Northern Virginia again offers a local example, where the Hillwood Square co-op in Falls Church sold itself after a two-thirds vote:

“They were faced with the prospect [of] spending a significant amount of money to upgrade the property’s underground infrastructure… ‘Hillwood was one of the most complicated as well as the most rewarding land deals we have had the opportunity to represent in our careers,’ [broker Mark] Anstine said in a joint statement”

A condominium next to the Huntington Metro has put itself up for sale via an RFP process, with an 80% approval threshold and a requirement that replacement units be built and offered to current residents first.

An interesting application of a cooperative scheme to urban redevelopment challenges could involve capitalizing new cooperatives with existing smallholdings, or redeveloping part — but not all — of a co-op. A co-op, as a stock corporation, has relatively few restrictions on its property holdings and financial activities — especially compared to a non-profit condominium association, which typically would have to distribute excess funds to members.

Land assembly for major projects in Japan, like Roppongi Hills, can be undertaken by pooling properties together into a “Redevelopment Association.” By guaranteeing equity participation in the new development (and new on-site replacement housing), this approach ensures that landowners share equally and fairly in property value gains — thereby removing individual owners’ worry that they sold out too early/cheaply.

Cohabitation Strategies included an equitable-growth idea similar to this strategy — what it called “Cooperative Housing Trusts” — in MoMA’s recent “Tactical Urbanism” exhibit. These community land trusts could aggregate and sell otherwise unusably-small quantities of air rights, and reinvest the proceeds into permanently affordable housing. (It was the one interesting idea in the entire exhibit, IMO.)

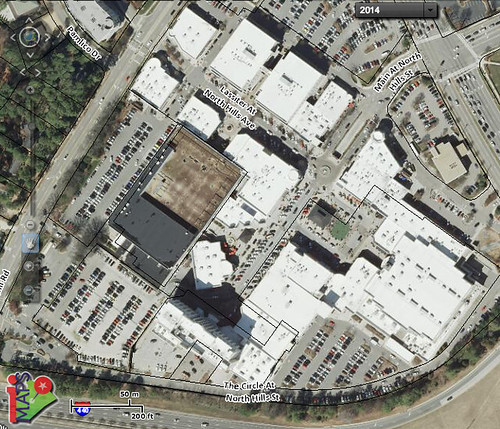

* No examples come to mind off-hand, but this is a common practice in shopping mall redevelopments. Department stores that own their own land have been excluded from many redevelopments that engulf them, as with the aging JCPenney at North Hills in Raleigh:

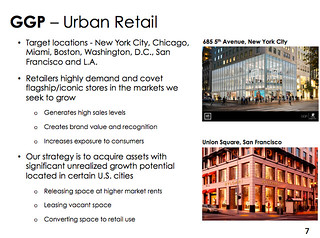

The opposite situation was bound to happen someday, and of course it’s flailing-about Sears that is leading the way. It’s not just subdividing its boxes and adding new subtenants like Whole Foods, but in at least two cases (at Aventura, North Miami’s fortress mall, and Metrotown outside Vancouver) it’s going rogue and doing its own mini-de-malling without permission from its “landlord.” Sears’ footprint at Aventura will shrink almost 90%, to just 20,000 feet — maybe their agreement with Simon requires that they not abandon the site entirely.