Take a photo tour of DC’s MLK Library

With the architectural future of DC’s central public library, the Mies van der Rohe-designed Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial Library, currently being debated, I’m sharing presentation notes I wrote up for a recent historic preservation class — both a critique of MLK as a work of art, and a timeline of the recent (and still somewhat ongoing) controversy over preserving it as a library.

Overview & Program

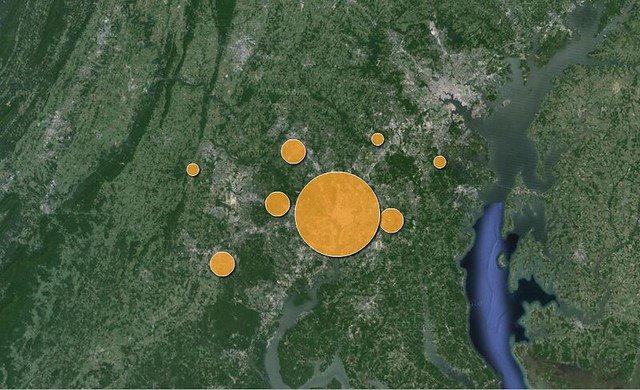

9th & G NW at Gallery Place. 400,000 sq. ft., 3 basements (including parking, storage, meeting rooms) & 4 above ground levels

Constructed 1968-1972 — began just before riots following MLK’s assassination touched even downtown DC, leading for calls to name library after King. (Was only memorial to King in DC from 1970-2011.) Mies died in 1969; other buildings were also in the pipeline but finished before, so this was “last Mies building.” Building is <40 years old (usual cut-off for National Register designation)

Replaced a Carnegie library on Mount Vernon Square (MVS), now home to the local historical society and used as event space.

Has always been DC’s central library, housing numerous special collections and programs including Washingtoniana on 4th floor, civil rights history, children’s, and adult literacy

The International Style

In Poppeliers et al, 92: “Concrete, glass and steel… Bands of glass became as important a design feature as the bands of ‘curtain’ that separated them… Balance and regularity… Cantilever and ground-floor piers”

International Style elements prominent in King library include an emphasis on the structural grid flowing inside and outside the building, wrapping around building with the I-beam mullions. Material palette is classic “less is more” Mies, honestly expressing the structure: black painted steel panels and beams, clear/bronze glass, tan brick, terrazzo and granite floors (no travertine, though), Helvetica Extended font on signage

The building displays many hallmarks of Miesian design (see this great MoMA online exhibit), particularly in its palette of materials, proportions derived from the golden ratio, and the use of ornaments like I-beam mullions. The quintessentially Modern design draws attention to its glass curtain walls and to the seamless flow between interior and exterior design elements through its large expanses of glass — most notably in a recessed ground floor lobby space that extends outside. (Gallery of Mies van der Rohe building photos.)

This is the only Mies mid-rise that I’ve seen; everything else is 1-2 stories or a skyscraper.

Interesting to note that architecture had largely moved on from Mies’ studious minimalism by 1972, embracing sharper angles, a wider palette of materials, and even some decorative flourishes. This was a bit old-fashioned at the time.

History, Threat, Controversy

1972 (Sep): building dedicated

1976: Air conditioning and heating both fail, temporarily closing library twice

1998: Anthony Williams, then CFO of DC (appointed by President Clinton) wins election as mayor, succeeding Marion Barry; Control Board cedes back executive authority. Launches several large construction projects, including Washington Convention Center [2003] and Nationals stadium [2006]

1999: pedestrian mall along G St removed

2003: Williams reported to be interested in $150M new library at old convention center site.

- Construction began on new convention center (C.C.) north of MVS, opening up site of old C.C. (south of MVS) for development. City owns both C.C. sites.

- Hines consortium selected to develop old convention center site, included civic use in program.

- 9th & G was revitalizing, and the corner would be sought after for retail, office, or another cultural use — numerous office redevelopments along 9th St, many recent retail and private museum developments along G: renovated Portrait Gallery, Spy Museum, Crime & Punishment museum, Verizon Center, Hotel Monaco, etc.

- Many other cities (particularly in West) have built grand new central libraries as part of downtown redevelopment schemes, reflecting new library programs: Seattle (Koolhaas), San Jose, Salt Lake, Denver, Minneapolis, Montreal, Vancouver BC. Interestingly, many of these cities were replacing Brutalist libraries also built circa 1970.

2004: Williams convenes Future of Public Library System task force. DC Preservation League, in nominating the site to its 2004 Most Endangered List: “[T]he only building in Washington, DC by any of the ‘big three’ (Mies, Wright, and Le Corbusier) Modernist architects. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library has stood as the only monument to Dr. King in the nation’s capital for the past 30 years… the only [library] ever designed by Mies, was constructed with a flexible interior plan and the capacity to add a fifth story when needed…”

2006 – The big push by Williams

- January: task force appointed by Williams recommends $450M overhaul of libraries, including $280M for new central library (includes $100M opportunity cost of taking site from Hines) and $170M for neighborhood libraries. “Besides being depressing, and aside from all the deferred maintenance, the Mies building is a very inefficient building,” said developer Richard Levy, who heads the library board’s facilities committee.

- February: federal budget includes $30M match for $70M in local funds for library system construction. (Laura Bush was a librarian.)

- May 1: Library Transformation Act introduced by Mayor Williams into Council, requires “preserves the historic character of the building.” Estimated revenue of $60M from a 99-year lease + $50M from a 30-year PILOT (TIF-like mechanism that applies to leased land), leaving a $70M funding gap for the new library, to be filled by $40M TIF + $14M federal. Referred to council committee, not voted out

- May 2: Hines unveils master plan for old convention center site, includes 2.5 acres for “potential new library”

- Summer: Public Library Foundation solicits additional schemes (e.g., adding wings surrounding Carnegie Library)

- Summer: DC Preservation League & Committee of 100 nominate library as landmark, raise concern over cost of new library

- September: Adrian Fenty wins Democratic mayoral primary (and general election in November); during campaign, supported Williams plan for new central library

2007 – Fenty backs down

- January: elevator replacement begins (they last worked in 2001)

- Spring: discussions begin with library, HPO, and “interested groups”

- June 27: Fenty shelves new library plan, report on library repairs

- June 28: HPRB unanimously votes to list King Library as landmark, forwards to National Register; library director testifies in favor

- July: elevators fixed

- September: MLK Design Guidelines Committee formed, DC Public Library Foundation retains firm to draft Design Guidelines

- November 22: added to National Register (building is 35 years old)

Key Issues

- Does a building under public ownership need to be landmarked?

- Are public owners necessarily good stewards? Will they respect design guidelines to shape future updates?

- Can a public owner perform “demolition by neglect”?

- How can public owners benefit from preservation incentives, since tax incentives mostly apply to rented commercial buildings?

- How do assumptions about construction costs shift public dialogue about preserving historic structures?

- Are construction costs for replacement vs. rehab comparable?

- Are all well-used public buildings going to become landmarks?

- Do “keystone” public buildings need to be new in order to have an economic development impact? Is it easier to finance new buildings? Is TIF/PILOT funding transferable between sites?

Rationale for Preservation

The King library is a unique example of a mid-rise Mies building, besides the numerous other “only” distinctions that it holds. It deserves the protection of local and national historic recognition, as a locally unique example of the 20th century’s most notable architectural style. As a “universal space,” it is uniquely capable of adapting to changes in library programs as media continue to evolve; it was designed with the flexibility to last 150 years.

Unfortunately, accretions over the years have diminished the interior’s openness — a hallmark of Mies’s low-rise pavilion structures. However, these can be repaired and likely will, given the library’s renewed commitment to design.

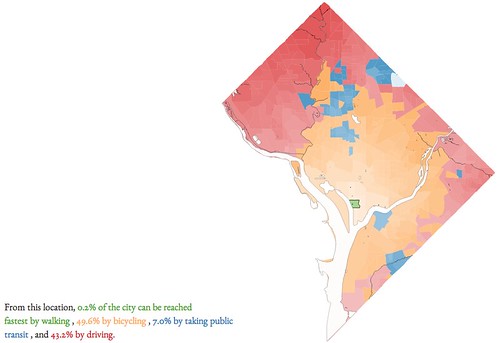

DCPL recently initiated renovations, replacements, or expansions at 15 branch libraries, including historic buildings in Georgetown and Mount Pleasant. Several of the new libraries have very striking modern designs, including those in Shaw and Ward 7.

Kennicott writes in the Post: “Mies’s vision was symbolically perfect — at the time — for a library. It emphasizes a clear view into a glass box for books… These layers of accumulation, each a small response to a community need, deprive the building of the silence it needs to speak clearly. The rhythm of Mies’s black I-beams, which give the tiers of windows above street level their basic meter, can’t be heard against the low but constant cacophony of competing messages that have been attached to the building.”

Still, is Mies’ Universal Space really functionally suitable as a library? The reading rooms are nice, and it has many library-specific features like book elevators (dumbwaiters), but:

- Dark, undersized corridors in interior of building

- Circulation confusingly hidden along back or sides of building — most of the new libraries handle circulation very well, epitomized by Seattle’s glowing escalators

- Stacks exposed to light (even indirect, bronzed glass)

- HVAC problems over the years contribute to deterioration of materials

- Owners don’t have resources to maintain fixtures/furniture, fix or replace systems

- Potential energy efficiency implications of old glass

- “Covered front porch” attracts vagrants; there’s no way to better activate the space without compromising the front wall of building

Stipe’s prologue provides a few rationales that might apply to a defense of MLK Library:

- “1. Physically link us to our past” — libraries are places of great collective memory

- “4. Relation to past events, eras, movements, and people” — MLK memorial, an International Style exemplar in a prominent location, and a formidable investment in Downtown DC at a time of precipitous decline

- “5. Intrinsic value as art, designed by some of America’s greatest artists” — only structure in DC by a world-leading Modernist architect (well, except maybe Breuer)

Stubbs, on the other hand, argues “To save the prototype” and only the prototype: “There can only be one true original of an authentic work of art, although copies can be made.” The King library is one of many of Mies’s works, and not his best; it suffers in many ways. It’s an adept copy of Mies’ groundbreaking high-rise or pavilion works, but it suffered from a shortchanged budget and the form (reminiscent of a truncated Mies high-rise) is too unwelcoming for use as a library, which involves extensive internal circulation. Stubbs takes a rather dim view of modern architecture in general: “Tens of millions of buildings from this period are found throughout the world; many have neither proven durable nor served their inhabitants well… In the early years of the world’s adoption of the International Style, protection of interior spaces from direct sunlight… was minimal or nonexistent…”

Bibliography

Philip Kennicott, “Mies’s modernist D.C. library building is getting a complementary companion,” Washington Post, May 30, 2010, E09.

“Most Endangered Places for 2004: Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Library,” D.C. Preservation League, accessed 5 September 2011, http://www.dcpreservation.org/endangered/2004/mlklibrary.html

John C. Poppeliers, S. Allen Chambers, and Nancy B. Schwartz, What Style Is It (Washington: National Trust, 1983), 92.

R. E. Stipe, “Prologue: Why Preserve?” in A Richer Heritage: Historic Preservation in the Twenty-first Century (Chapel Hill: UNC, 2003), xxvii-xv.

J. Stubbs, “Why Conserve Buildings and Sites?” in Time Honored: A Global View of Architectural Conservation (Hoboken: 2009), 33-63

G. E. Kidder Smith, Sourcebook of American Architecture (Princeton: Princeton Architectural, 2000).

Alice Sinkevitch, ed., AIA Guide to Chicago, Second Edition (New York: Harcourt, 2004).

“King Library,” Docomomo, accessed 6 September 2011.

Kriston Capps, “For once in a public building in Washington, there is excellence throughout,” Grammar.Police, accessed 3 October 2011, http://grammarpolice.net/archives/000929.php

“CityCenterDC In The News,” Hines|Archstone, accessed 3 October 2011, http://www.oldconventioncenter.com/news_inthenews.php

“Designation Procedures and Criteria,” DC Preservation League, accessed 3 October 2011, http://www.dcpreservation.org/districtscrit.html

EHT Traceries, Inc., Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library Design Guidelines (Washington: DC Public Library Foundation, 2008?), 22-26.

Rob Goodspeed, “What Will be the Fate of Washington’s Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library?,” Goodspeed Update, accessed 3 October 2011, http://goodspeedupdate.com/2006/2051

Rob Goodspeed, “New Central Library Plans ‘Shelved’,” Goodspeed Update, accessed 3 October 2011, http://goodspeedupdate.com/2007/2113

“Library Transformation Act of 2006, Bill 16-734,” DCWatch, accessed 4 October 2011, http://www.dcwatch.com/council16/16-734.htm

“Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library the newest DC Landmark,” DC Preservation Advocate (DC Preservation League newsletter), Summer 2007, 1.

Elissa Silverman, “D.C. Library Gets Sorely Needed Lift,” Washington Post, July 24, 2007, B1.

Debbi Wilgoren, “Overhaul Urged For D.C. Libraries,” Washington Post, January 18, 2006, A1.

Debbi Wilgoren, “Libraries Could Get Federal Funding,” Washington Post, February 6, 2006, B1.