A version of this post was posted at Greater Greater Washington.

Nine years ago, the District of Columbia adopted a Comprehensive Plan to guide planning efforts throughout the city. At the time, the District’s population had just started to perk up after six decades of decline, and the plan reasonably foresaw that growth could continue into the future. Yet even though the District’s population has grown substantially, its housing stock isn’t keeping pace.

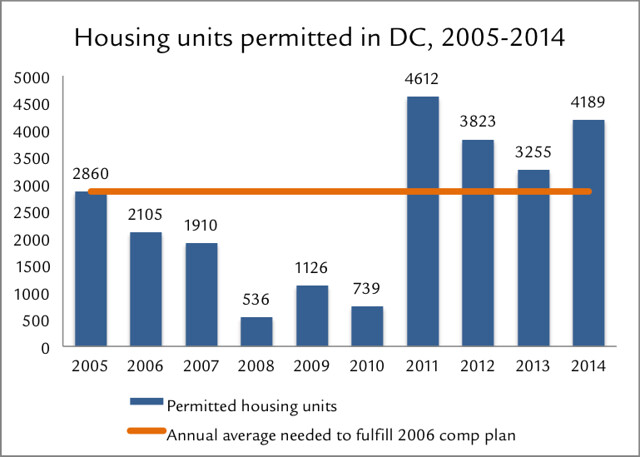

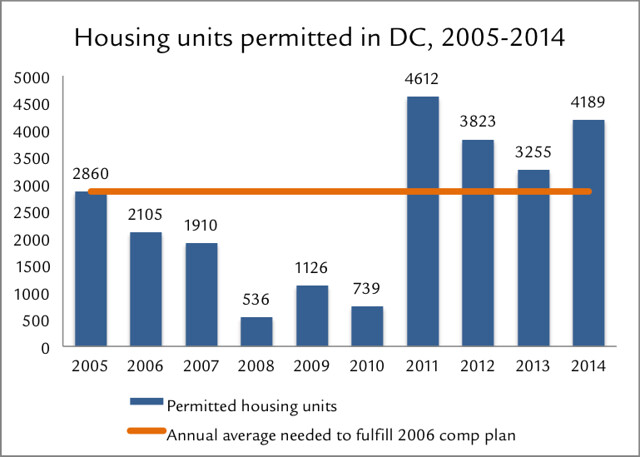

Three years before the comp plan was adopted, Mayor Anthony Williams pointed to recent population gains when he announced a bold goal to bring 100,000 new residents to the District within a decade [PDF]. The 2006 Comprehensive Housing Strategy Task Force recommended adding 55,000 new housing units over 20 years (a recommendation reaffirmed by a 2012 housing strategy update). Not only would that figure meet long-term population growth goals (accommodating 114,400 residents at the then-current household size of 2.08), but it seemed attainable: The District issued building permits to 2,860 housing units in 2005.

The comp plan incorporated much of the Housing Strategy, noting in its Housing Element that “The increase in [housing] demand has propelled a steep upward spiral in housing costs, impacting renters and homeowners alike… The housing shortfall will continue to create a market dynamic where housing costs increase faster than incomes.” To address the shortfall, the plan’s very first policy opens with the statement: “The District must increase its rate of housing production if it is to meet current and projected needs through 2025 and remain an economically vibrant city,” and raised the forecast slightly, to 57,100 additional housing units over the plan’s 20-year horizon.

The city as a whole isn’t meeting its goals

Yet despite all the new construction over the past decade, including two building booms, DC’s currently on track to miss its 2025 goal by 13%. Instead of building 2,855 units per year, DC’s averaged fewer than 2,500 each year over the past decade.

The big reason why is that homebuilding nationally came to a near-standstill during the 2008 crisis, and the District was no exception: building permits crashed by 81% from 2005 to 2008, and remained at low levels through 2010. Many proposed projects, like CityCenterDC and Half Street, came to a halt when banks collapsed. Yet all that time, the city’s population, and thus the demand for new housing, continued to grow.

Construction has since rebounded to new highs, with 39% more building permits issued each year between 2011 and 2014 than in 2005. Still, the new boom hasn’t yet erased the 3,000-unit backlog from the slow years.

To get back on track, building permits would have to keep up at recent years’ record-setting pace for at least another three years — and perhaps longer, since the next ten years will also inevitably include another economic slowdown that will subdue construction.

Housing growth has lagged population growth

Even though housing construction has lagged projections, the city’s population has continued to grow. Instead of moving into new housing, all of these new residents have in recent years just filled holes in the existing housing stock.

Vacant units — the slack in the District’s housing market — have steadily disappeared in recent years. Between 2010 and 2013, the Census reports that the number of vacant housing units in the District plummeted by 13,319 (or 31%), far outpacing the 6,850 units that were added to the District’s housing stock.

It’s convenient that so many vacant housing units just happened to be available just when the District’s population began booming, but that feat can’t continue forever. A growing population will, at some point, require new housing.

Indeed, current market indicators show that there’s still tremendous demand for newly built housing: Even though a record number of new apartments have been built, they’re being snapped up as soon as they’re available.

The recent slowdown in the District’s population growth isn’t reason to rest: It could be that slower population growth is a result of inadequate housing growth. Slower population growth largely results from reduced domestic migration, and the #1 reason behind domestic out-migration from DC is because of its inadequate housing. (No surveys track why people choose not to move to DC in the first place, but the reasons are likely similar.)

Yet meeting local environmental goals requires even more population, and housing

David Alpert’s article on Sunday referred to the District and the greater Washington region’s aspirations to a greener future, which require that the District add many more residents. DC’s Sustainable DC Plan, which was adopted in 2012, acknowledges that the District needs to “increase urban density to accommodate future population growth within the District’s existing urban area,” and sets a target of welcoming 250,000 new residents by 2032. That target implies at least 100,000 new housing units, a figure confirmed by recent studies from George Mason University and echoed in the region’s long-range plans.

Adding more residents to the region’s core will result in a substantially smaller environmental impact than adding those residents at the region’s edges. Accommodating more population growth within existing built areas, like the District, reduces the overall environmental impact of new development, and not only by diverting pressure to pave over outlying wildlife habitat and green space.

People who live in dense settings close to the regional core live more lightly on the earth as a matter of course: Residents of the urban core drive less than half as much as residents of sprawling suburbs — a fact that regional transportation plans rely upon to keep traffic congestion, and road expansion, down.

DC can take a fresh look at housing

As Alpert wrote on Sunday, “a great opportunity” to review DC’s housing needs “will come when the District begins the process of revising its Comprehensive Plan.” As part of that review, the Office of Planning should examine the comp plan’s policies in light of the District’s new, more ambitious goals — and the District’s failure so far to deliver sufficient new housing to meet demand.

Yet it’s getting harder, not easier, to build new housing in the District. New zoning restrictions, like the “pop-up ban,” have made it even more difficult and costly to build new housing units in large swaths of the District. Even when proposed developments meet existing zoning, they often face costly and time-consuming litigation.

Since the comp plan guides the zoning regulations, a revised comp plan should guide future zoning changes to make it easier for the District to meet its housing and environmental goals. A revised comp plan should also determine where new housing can and should go; a future post will show how the existing comp plan has fallen short in that regard.