My recent five-day bike tour through the mountains whetted my appetite for quicker escapes into the same countryside. Luckily, the DC region sits astride the fall line, which puts a variety of topographies within reach. This makes it possible to do a bike overnight, or more ambitiously, a sub-24-hour outing (S24O).

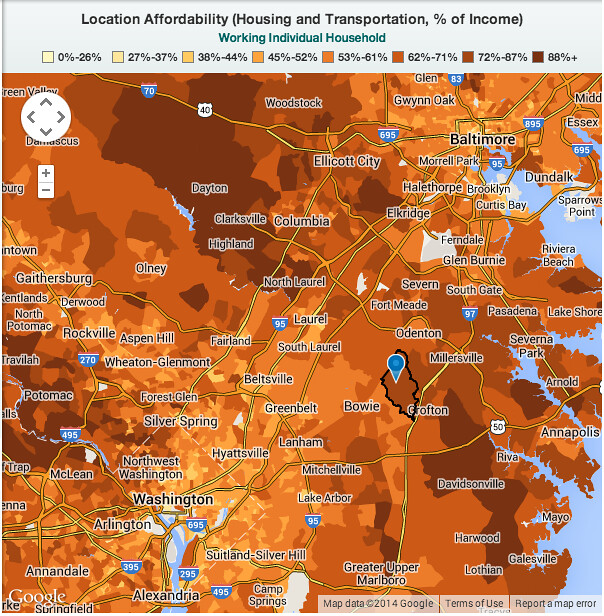

On such a short trip, it’s important to ride enough miles to make the trip an accomplishment, but not so many as to be exhausted or to preclude any off-bike adventures. One key to doing so is to strictly limit the mileage spent biking down dangerous streets in traffic-choked suburbs, and to take advantage of trails — particularly easy-grade rail or riverfront trails.

One weekday-only trip that combines these, starting in the District, is a bike trip from Poolesville, Md. to Harpers Ferry, W. Va., returning via the C&O Canal towpath along the Potomac. This takes advantage of Montgomery County’s urban growth boundary, the area’s extensive rush-hour bus system, and the centuries-old Potomac path.

One recent day, I awoke at 5 AM to board a Red Line train at 6 AM, leaving the system at Shady Grove just as the morning bike ban started. From there, I waited a few minutes for RideOn route 76, which on weekday peak hours travels from Shady Grove through Kentlands, then deep into the Ag Reserve, and eventually ends in the rural town of Poolesville. Like all RideOn buses, the buses sport dual bike racks. Interestingly, the largest business in downtown Poolesville is a tractor supply store — the last place I expected to be able to take a city bus to.

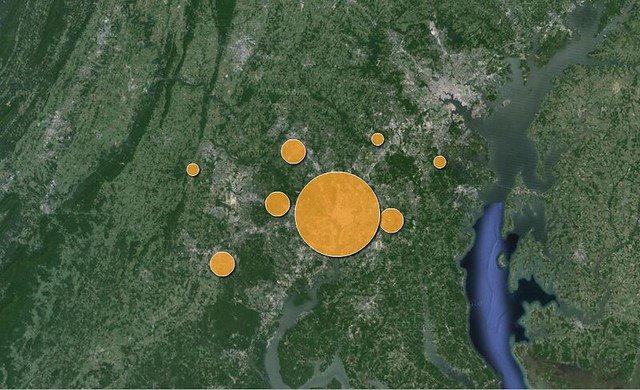

Poolesville is famous among area cyclists as a jumping-off point for rides on country roads, but I wasn’t aware of any car-free routes to get there until I scrutinized WMATA’s regional bus maps.

From Poolesville, it was a quick 5 1/2 mile, downhill ride down Whites Ferry and Wasche Road to the Dickerson Conservation Park, and then onto the C&O. Harpers Ferry is another 22 miles upriver, not far past the railroad-centric town of Brunswick, Md. Equally charming Shepherdstown, W.Va. is another 13 miles upriver.

Lodging and camping options along the way are plentiful. Shepherdstown and Harpers Ferry offer numerous B&Bs and hostels, while the C&O has walk-in campgrounds every few miles along the trail plus six historic cabins available for nightly rentals.

The return bike trip is all downhill, and can be accomplished in one day: It’s 61 miles from Harpers Ferry to Georgetown, or 73 miles back from Shepherdstown. 13 miles can be shaved by hopping across the river at White’s Ferry and picking up the W&OD trail in Leesburg, which also has a charming downtown, and ending at the Silver Line. (Even with just Phase 1, Silver extends further than any of Metro’s rail lines.)

Another, 7-day-a-week transit option that I’ve used is Metrobus B30 — yes, the BWI bus. It, too, has bike racks just like every other Metrobus, but unlike other Metrobuses it travels beyond the Patuxent River and into metro Baltimore. (This option takes much longer than MARC, which may soon add a bike car to its Penn Line weekend trains.)

From the BWI light rail station, a cyclist can:

- Board a Baltimore light rail train into the city, with its fantastic neighborhoods and Olmsted trails — or to Hunt Valley, about half a mile short of the Northern Central Rail Trail north to York;

- Connect to several other buses, notably MTA’s buses to Annapolis or RTA’s buses through Howard and Anne Arundel counties;

- Ride up alongside the tracks to the BWI Trail and follow the signs to the B&A Rail-Trail to Annapolis and the Chesapeake shore;

- Walk through the BWI Amtrak station, then ride north on Ridge Road and through old downtown Elkridge (not much there) to the Patapsco Valley state park’s trails and thence to Ellicott City.

(That said, biking all the way to Baltimore or Annapolis is certainly feasible. I’ve used Brock Bridge Road for the former, and Governors Bridge Road for the latter, and enjoyed a relatively low-stress trip. Next up: Metrobus to Olney, then riding via Columbia and Catonsville to Baltimore.)

Someday, urban cyclists in DC will be able to easily slice past the sprawl aboard commuter trains. It’s possible today to bring bikes aboard VRE midday trains, which makes it possible to leave early on Friday and ride back from Manassas or Fredericksburg. Another option to consider is VRE halfway, then a ride through the farms to Charlottesville (from F’burg or Manassas).

The region’s weekday commuter buses might also prove useful, although they’re certainly not geared to weekending cyclists. Loudoun Transit runs to Purcellville, aka the western end of the W&OD Trail, and appears to allow bikes for pre-registered users. Maryland’s commuter buses cover a vast territory from Hagerstown to the Eastern Shore, but have no specific bike policy.