In the fable of the Three Little Pigs, one pig builds a house from straw, a second from sticks, and a third from bricks, with very different consequences. Notably absent from the pigs’ tale is any mention of each little pigs’ construction budgets. For humans living in the 21st century, it’s not protection from hyperventilating wolves, but rather out-of-control budgets, that determine our choices of building materials.

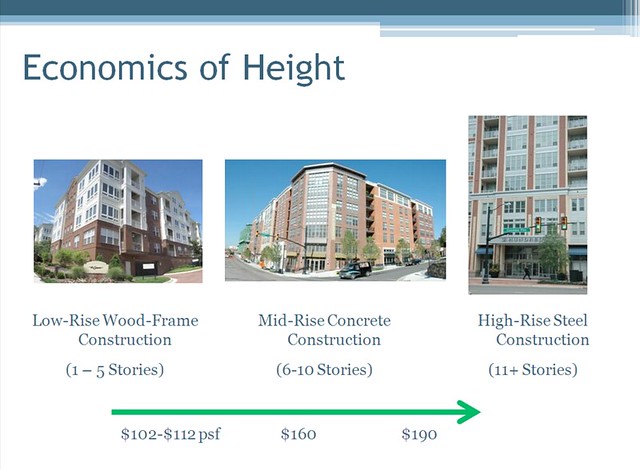

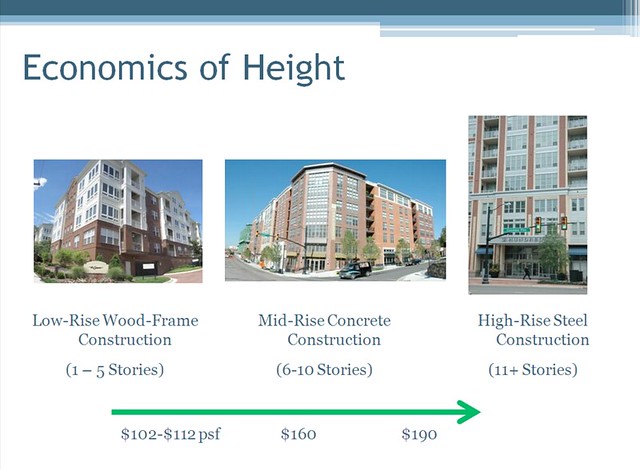

The Height Act limit for construction in outlying parts of Washington, DC, enacted back in 1899, is 90′ — effectively 7-8 stories. This particular height poses a particularly vexing cost conundrum for developers seeking to build workforce housing in DC’s neighborhoods, since it’s just beyond one of the key cost thresholds in development: that between buildings supported with light frames vs. heavy frames. Heavy frames rely on fewer but stronger steel or reinforced concrete columns to hold up the building, and are better known as Type I fireproof structures. Light frames rely on many small columns (usually known as studs), and are usually referred to as Type II (if masonry or metal) or if wood, Type III (with fire resistive treatments), Type IV (if made from heavy beams), or Type V (if little fire-proofing has been applied) construction.

[Type I: CityCenterDC, photo by David Gaines/Flickr]

[Type III: Takoma Station, photo by author]

[Type III: stick over concrete podium on 9th St. NW, photo by author]

These structural types are rated using the degree of fire protection that these structures offer, with lower numbers denoting more fire-resistant structures. In DC, they’re defined in the city’s building code, which is based on an international standard — the International Code Council (ICC) and its “I-Codes.”

The ICC’s Table 503 sets limits on how high different types of buildings can be. Thanks to technological improvements to wood and fire safety improvements to buildings, mid-rise buildings can be built up to five floors high using Type III construction. These five floors can, in turn, be placed atop a one-story concrete podium to build a six-story mixed-use building.

How much cheaper?

Light frame construction cuts costs in two principal ways. Light frames use fewer materials in the first place and thus have smaller ecological footprints, particularly since cement manufacturing is one of the most carbon-intensive industries. Light frames are built from standardized parts that are usually finished off-site, rather than on-site, so materials are cheaper, on-site storage and staging (e.g., cement mixers) require less space, and construction is faster — further reducing overall construction costs, since developers pay steep interest rates on construction loans.

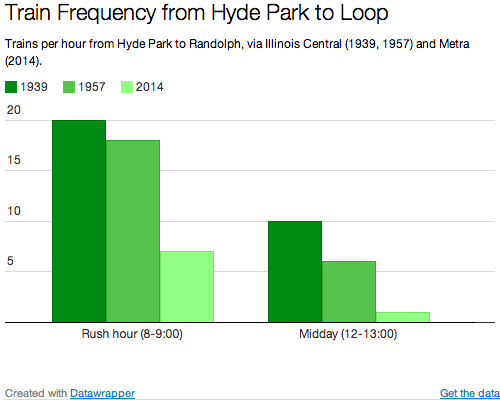

These cost savings really add up throughout the entire building. The ICC’s Building Value Data provides national average per-square-foot construction costs for multifamily of:

| $104.74 |

Type V |

Low-rise wood frame |

| $119.77 |

Type III |

Mid-rise wood frame, fire-resistant walls |

| $139.01 |

Type II |

Mid-rise, light-gauge steel |

| $150.25 |

Type I |

High-rise fireproof |

Similarly, the RS Means construction cost-estimator database provides 2012 estimates (adjusted for local prices in DC) that show an even steeper premium for high-rise construction:

| $136.70 |

Type V |

Low-rise wood frame, 3 stories |

| $162.87 |

Type II |

Mid-rise, light-gauge steel & block, 6 stories |

| $246.32 |

Type I |

High-rise fireproof, 15 stories |

As the ICC figures show, switching from Type III to Type I construction increases the cost of every square foot by 25.4%. Thus going from, say, a six-story building to seven stories only increases the available square footage by 16.7%, but increases construction costs by 46.3%. This results in a difficult choice: go higher for more square feet but at a higher price point, or take the opportunity cost, go lower, and get a cheaper, faster building?

In most other cities, the obvious solution is to go ever higher. Once a building crosses into high-rise construction, the sky’s ostensibly the limit. In theory, density can be increased until the additional space brings in enough revenue to more than offset the higher costs. As Linsey Isaacs writes in Multifamily Executive: “Let’s say you have a property on an urban infill site that costs $100 per square foot of land. Wood may cost 10 percent less than its counterpart materials, but by doing a high-rise on the site, you get double the density and the land cost is cut in half.”

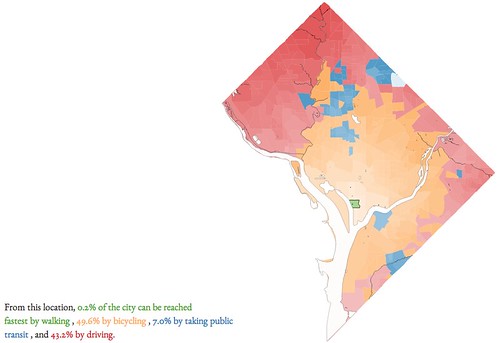

Yet here in DC, the 90′ height limit on residential areas, and commercial streets outside the core, tightly caps the additional building area that could pay for high-rise’s substantial cost premium.

Within the twilight zone

For many areas in DC, land is expensive enough to fall into a Twilight Zone. These areas are both expensive enough to require high-rise densities, but the local rents are too cheap to justify high rises’ high per-foot construction prices. These areas are not super-trendy like 1st St. NE in NoMa or 14th St. NW in Logan Circle, which are seeing an explosion of Type I construction (and prices to match, with new apartment buildings selling for $900/sq. ft.). Nor are they outlying areas, where developers think the opportunity cost of forgoing a future high-rise is acceptable and thus proceed with Type III construction. The recent apartment boom has given local residents a good, long look at Type III construction: in outlying city neighborhoods like Brookland, Fort Totten, Eckington, Petworth, off Bladensburg Road, and in suburban areas like Merrifield and White Flint.

In areas that are in-between, a lot of landowners are biding their time, waiting until the moment when land prices will justify a 90′ high-rise — a situation which explains many of the vacant lots in what might seem like prime locations. My own neighborhood of Southwest Waterfront is just one example. Within one block of the Metro station are nine vacant lots, all entitled for high-rise buildings — but their developers are waiting until the land prices jump high enough to make high-rises worthwhile amidst a neighborhood known for its relatively affordable prices. While the developers wait, the heart of the neighborhood suffers from a critical mass of customers within walking distance; the resulting middling retail selection, vacant storefronts, and subpar bus service reinforces the perception that Southwest Waterfront is not worthy of investment. Nearby Nationals Park is similarly surrounded by vacant lots, with renderings of nine-story Type I buildings blowing in the breeze.

In NoMa (east of the tracks) and the western end of H St. NE, projects like 360 H and AVA H Street were redesigned after 2008’s market crash so that they didn’t require Type I construction. The redesigns reduced costs, reduced the developers’ need for scarce financing, and made the projects possible — but also reduced the number of units built. AVA was entitled for almost 170 units, but was built as 138 units: building 20% fewer units cut structural costs by over 40%, according to developer AvalonBay.

Elsewhere, some other development projects have similarly been redesigned with faster Type III construction, even as future phases assume Type I construction. Capitol Quarter, the redevelopment of Capper/Carrollsburg near Navy Yard, might win an award for the shortest time between announcement and groundbreaking for the mixed-income Lofts at Capitol Quarter. Several blocks west, the first phase to deliver at the Wharf will be the last phase that was designed; in fact, the idea of redeveloping St. Augustine’s Church as a new church with a Type III residential building above came years after design began on the high-rises to its west. Rumor has it that across the street, a developer is redesigning an 11-story high-rise as a Type III building, foregoing five floors of housing in order to get to market faster.

New technologies can break the logjam

If it weren’t for the Height Act, developers wouldn’t just sit and wait on sites like these. They’d probably just build Type III buildings, and if there’s still demand, they could build Type I downtown towers with 20+ floors. But due to the Height Act, DC is one of the only cities in America where there’s a substantial market for 7-8 story buildings.

To break this logjam without changing the Height Act, DC’s building community can embrace new light-frame construction techniques that can cost-effectively build mid-rise buildings without the need for steel beams and reinforced concrete. Local architects, developers, and public officials could convene a working group to bring some of these innovations to market, and thus safely deliver more housing at less cost.

Cross laminated timber (CLT), a “mega-plywood” made of lumber boards laminated together, has sufficient strength and fire resistance for high-rise structures; it’s been used to build a 95′ residential building in London and a 105.5′ building in Melbourne. The ICC has approved CLT for inclusion in its 2015 code update — but the city has leeway to approve such structures today under a provision that allows “alternate materials and methods,” and cities like Seattle have started to evaluate whether to specifically permit taller CLT buildings.

[The Bullitt Center, a zero-impact building in Seattle, uses CLT for most of its upper-story structure.)

Type II buildings, often built with light frames of cold formed (aka light gauge) steel, can achieve high-rise heights but are limited by the ICC to the same heights as Type III. (For example, 360 H Street was re-engineered from Type I to Type II, and lost two stories in the process.) Prefabrication, hybrid systems that incorporate other materials, and new fasteners have made mid-rise Type II buildings stronger and most cost-effective. However, as the RS Means chart above shows, Type II might be cheaper than Type I but remains more expensive than Type I. Similar prefabrication has been applied to Type I mid-rises on the West Coast to reduce their costs.

By embracing these advancements in structural engineering, as well as providing relief from onerous parking requirements, DC could more easily and affordably build the mid-rise buildings that will house much of the city in the future.

(Thanks to Brian O’Looney, partner at Torti Gallas and Partners, for sharing his expertise. A version of this post was cross-posted at Greater Greater Washington.)