Redevelopment of Alexandria public housing near Braddock Metro in 2013. The slightly taller buildings with gables in the back include replacement units.

A subsequent conversation at CNU bemoaned how “tollbooth zoning” (as Ben Ross calls it) has turned everyone into their worst nightmare of a money-grubbing Chicago machine pol, rasping “ubi est mea?” over a cigar.

Ross’ description: “payment, in cash or in kind, is exacted from developers as the price of passage… The most common technique for forcing developers through the tollbooth is to zone for much less density than anyone really wants… When someone wants to build, they either apply for rezoning or seek approval of an ‘alternate’ use of the land” — and thereby pulls up to the tollbooth. It seems cost-less, but only because it’s a way current voters/residents can extract payments (tolls, ransoms) from future residents.

In Chicago, the racketeering operation was simple — you paid, you played. You want to build something? Fine, pay up and we’ll talk. (This indictment was a classic.) In many cities today, it’s pretty much the same. We’re systematically under-zoning (and over-planning) everything to maximize the possible value granted through zoning relief, and demanding the difference back through legalized bribes we call community benefits agreements.

Because the contents of the CBA or PUD are up for negotiation at one point in time, communities end up with whatever’s convenient then, not what’s actually needed. The results can be baffling. One local municipality has a surfeit of tiny “black-box” theaters that don’t get used, since theaters can only be purchased in increments of one, and the cheapest performing-arts giveaway is a black-box theater. (Someday, I’ll pull together a tour of the laughable “arts spaces” that zoning’s required around Penn Quarter.)

The most obvious solution would be to buy upzones using cold, hard cash on a per-foot basis, but that’s not allowed — if it’s a tax (or impact fee), it requires a legal nexus. [Update: Of course, Chicago has since devised a cash-for-upzoning scheme. Don’t try this at home.] So instead, communities get whatever the developer feels generous enough to give. Not to mention that the entire process, since it’s all boils down to political power, favors those who already have political power — large, well-connected developers vs. squeaky-wheel communities. Small developers get shut out of any opportunity to build, and disempowered communities (the homeless, for instance) never get a chance.

Now, since we’ve established that the zoning is entirely arbitrary anyways, why not flip the equation and start with the community benefits? The quantity of stuff permitted on the site ultimately doesn’t matter as much as the quality of what goes there.

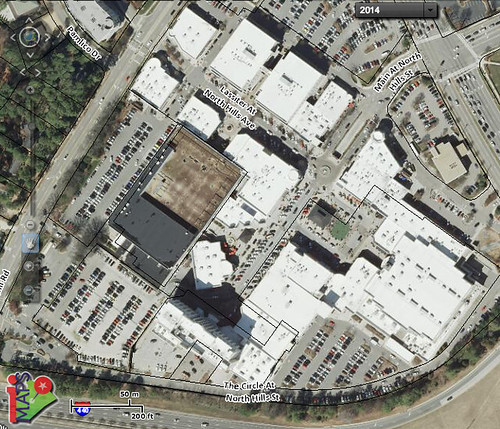

This “upside down pro forma” is already being done in several instances, notably in situations where municipalities are seeking to maximize affordable housing output. For instance, cities that have committed to 1:1 public housing replacement — as HUD’s Choice Neighborhoods program does — have long had to work backwards to find enough market-rate units to make the pro forma pencil out. Alexandria has operated under a 1:1 public housing replacement policy since 1972 (“Resolution 830,” PDF), and the results are very impressive — seamlessly integrated urban fabric, both socially and physically.

Canada never had HOPE VI as federal policy, and its municipalities have a firmer hand in land use control. (For instance, Ontario’s Section 37 permits cash payments within a negotiated CBA. Sounds filthy, but actually cash is nice in that it’s easily measured.) So, working backwards from the benefits to the proposal isn’t unusual.

In Vancouver, the mind-bogglingly complex Woodward’s redevelopment used a public RFP process to stack a vertical mixed-use community with just about everything onto an abandoned department-store block right on Skid Row.

In Toronto, zoning bonuses paid for a 68-unit artist live/work space. Regent Park’s redevelopment has created 1:1 replacement units, plus 15% so far. As part of the development agreement, space for social infrastructure was built early on; the Daniels Spectrum “includes several state-of-the-art performance spaces, a locally run café, a green roof, and two floors for various educational, arts and community groups that have long operated in and around Regent Park. Many relied on informal or rented space, and some had been uprooted when the demolition began. The need for this kind of social infrastructure remained.”

Regent Park in Toronto, where a commitment to better than 1:1 replacement housing (and additional retail and social services) is resulting in much higher densities.

That’s certainly one approach for maximizing the community benefits, but it introduces a few huge risks. It still only works for huge projects, it still relies on political power, and it still subjects the CBA to the fads of the moment. And what happens if the approach fails? The developer might just decide there’s nothing in it and walk away. (Another argument for good phasing.)

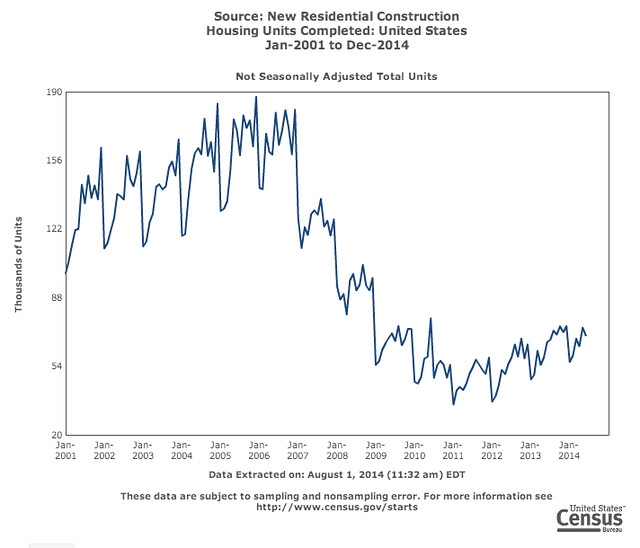

Even though the “tollbooth” system is the one we’re used to, it’s in large part to blame for making development complicated and costly — thus shutting out smaller producers, resulting in under-production and higher costs for everyone. Those higher costs go into landlords’ pockets. A rational system would instead make it easier to build, lower housing prices, and instead steer the same dollars to higher taxes and better services for all needy people, regardless of whether they live near a CBA-extracted theater or not.

To finish off the analogy: instead of fighting over who gets to sit inside the tollbooth, maybe it’s time to replace tolls with VMT charges and carbon taxes.

(Updated 4/2018)