Most American downtowns are surrounded by “parking craters,” as Streetsblog has termed them. Here in DC, downtown’s successful redevelopment has almost eliminated downtown parking craters, with one key exception. This success hasn’t completely eliminated parking craters from DC, though — it’s just moved them outside downtown.

DC’s last privately-owned parking crater has a very unusual backstory. Gould Property owns the site free and clear, but only due to a land swap to get the Marriott Marquis built two blocks north. Gould had purchased part of the Marriott site back in the 1990s, when prices really were cheap enough to justify parking craters. The land basis and opportunity cost on this site is unusually low, especially since the former building on the site could not have remained.

Most surface parking lots are built as what zoning calls “an accessory use,” which means they’re an “accessory” to something else on the same lot. The parking lot at Sam’s Park & Shop in Cleveland Park or the Capitol’s parking lots, are “accessory” parking lots.

Parking craters, on the other hand, are usually not accessory parking directly tied to another land use; they’re paid parking lots whose owners are holding onto land that they speculate could be a future development opportunity. A parking lot requires minimal maintenance, but pays out some income in the interim. Most importantly, a parking lot is “shovel ready” — unlike a building with tenants in place, whose leases might or might not expire at the same time, a parking lot can be emptied and demolished on short notice when opportunities arise.

High rents and short buildings limit speculation

The opportunity that many “parking crater” developers are waiting for is the chance to build a big office tower. Offices pay higher rents to landlords than apartments (although in the best locations, retail or hotels can be even more valuable). However, the banks who make construction loans to developers rarely allow new office buildings to be built before a large, well-established company has signed a long-term “anchor tenant” lease for much of the new building’s space. If the building isn’t pre-leased, the result can be a bank’s worst nightmare: a “see-through tower” that cost millions of dollars to build, but which isn’t paying any rent.

Within downtown DC, robust demand and high rents mean that landowners face a very high opportunity cost if they leave downtown land or buildings empty for a long time. Instead of demolishing buildings years before construction starts, developers can make room for new buildings by carefully lining up departing and arriving tenants, as Carr Properties did when swapping out Fannie Mae for the Washington Post.

Less often, a developer will build new offices “on spec,” or without lease commitments in place. A spec developer usually bets on smaller companies signing leases once they see the building under construction. Downtown DC has a constant churn of smaller tenants (particularly law firms and associations) that collectively fill a lot of offices, but few are individually big enough to count as anchor tenants.

Because office buildings in DC are so short, they’re relatively small, and therefore the risk of not renting out the office space is not that high. In a city like Chicago, by contrast, few developers would bother building a 250,000 square foot, 12-story office building to rent out to smaller tenants. Instead, they could wait a few more years and build a 36-story building, lease 500,000 square feet to a large corporation, and still have 250,000 square feet of offices for smaller tenants.

While height limits certainly constrain the size of offices in DC, other cities with much less stringent height limits have also managed to eradicate most of their parking craters. Boston and Portland are similarly almost bereft of parking craters within their cores, not because of Congress but because other planning actions have maximized predictability and minimized speculation. In both cities, small blocks and zoning-imposed height limits of ~40 stories (!) encourage construction of smaller office buildings

Another factor common to these cities are policies also encourage non-car commutes — Boston even banned new non-accessory parking downtown — and rail transit that distributes commuters through downtown, rather than focusing access along a freeway or a vast commuter rail terminal. Metro’s three downtown tunnels, and DC’s largely freeway-free downtown, help to equalize access (and property values) across a wide swath of land. In retrospect, it’s impossible to identify which one factor had the greatest effect.

This customer is always right

There is one big anchor tenant in DC’s office market: the federal government. The government has some peculiar parameters around its office locations, which also help to explain where DC does have parking craters.

Private companies often don’t mind paying more rent for offices closer to the center of downtown, which puts them closer to clients, vendors, and amenities like restaurants, shops, or particular transit hubs. The government, on the other hand, has different priorities: it would rather save money on rent than be close-in. The General Services Administration, which handles the government’s office space, defines a “Central Employment Area” for each city, and considers every location within the CEA to be equal when it’s leasing offices. It also usually stipulates that it wants offices near Metro, but never specifies a particular line or station.

As rents in prime parts of downtown rose, the government began shifting leased offices from the most expensive parts of downtown to then-emerging areas. Large federal offices filled new office buildings in the “East End,” helping to rejuvenate the area around Gallery Place and eliminate many parking craters.

This one rule scattered “parking craters” all around DC, but they’re steadily disappearing

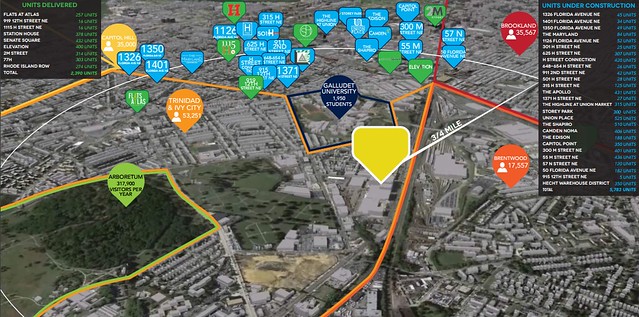

Over the years, DC noticed the success it found in broadening the federal government’s definition of the Central Employment Area, thereby spreading federal offices to new areas. It successfully lobbied GSA to widen the CEA further, encompassing not just downtown but also NoMa, much of the Anacostia riverfront, and the former St. Elizabeth’s campus. Because the latter areas have much cheaper land than downtown DC, and lots of land to build huge new office buildings, federal offices are now drifting away from the downtown core.

A developer with a small site downtown usually won’t bother to wait for a big federal lease: the government wants bigger spaces at cheaper rents. It’s easier to just rent to private-sector tenants. However, a developer with a large site within the CEA and next to Metro, but outside downtown, has a good chance of landing a big federal lease that could jump-start development on their land — exactly the formula that can result in a parking crater.

One recent deal on the market illustrates the point: the GSA recently sought proposals for a new Department of Labor headquarters. GSA wants the new headquarters to be within the District’s CEA, within 1/2 mile walking distance to a Metro station, and hold 850,000 to 1,400,000 square feet of office space.

The kicker is the timeline: GSA wants to own the site by April 2018, and prefers if DC has already granted zoning approval for offices on the site. It would be difficult for a developer to buy, clear, and rezone several acres of land meeting those requirements within the next two years, so chances are that the DOL headquarters will be built on a “parking crater” somewhere in DC. Somewhere outside downtown, but within the CEA, like:

- “Spooky Park,” or Parcel A at The Yards, formerly the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency offices across from the Navy Yard Metro. It’s zoned for 1.8 million square feet of offices, and is probably the largest single parking crater in DC.

- Behind the Big Chair in Anacostia are several parking lots that could house a million square feet of offices.

- The Portals, next to the Mandarin Oriental Hotel at 14th and D streets SW, has two empty lots left. A residential tower will soon sprout on one, but the other is being reserved for another office building, across from to another building that was built for the FCC, but which will soon be vacant.

- The two blocks just west of the Wendy’s at “Dave Thomas Circle,” in the northwest corner of NoMa, are owned by Douglas Development and Brookfield Asset Management. Brookfield’s site could house 965,000 square feet of development, and Douglas’ site could have a million square feet.

High-rise residential seems like it would be an obvious use for land like the Yards, which is outside downtown but atop a heavy-rail station. Yet even there, where one-bedroom apartments rent for $2,500 a month, it’s still more valuable to land-bank the site (as parking, a small green area, and a trapeze school) in the hopes of eventually landing federal offices.

Many federal leases are also signed for Metro-accessible buildings outside the District, which helps to explain why prominent parking craters exist outside of Metro stations like Eisenhower Avenue, New Carrollton, and White Flint. (For its part, Metro generally applauds locating offices at its stations outside downtown, since that better balances the rush-hour commuter flows.)

One reform could fix the problem

One esoteric reform that could help minimize the creation of future parking craters around DC is to fully fund the GSA. Doing so would permit it to more effectively shepherd the federal government’s ample existing inventory of buildings and land, and to coordinate its short-term space needs with the National Capital Planning Commission’s long-term plans.

Indeed, GSA shouldn’t need very many brand-new office buildings in the foreseeable future. Federal agencies are heeding its call to “reduce the footprint” and cut their space needs, even when headcount is increasing. Meanwhile, GSA controls plenty of land at St. Elizabeth’s West, Federal Triangle South (an area NCPC has extensively investigated as the future Southwest EcoDistrict), Suitland Federal Center, and other sites.

However, ongoing underfunding of GSA has left it trying to fund its needs by selling its assets, notably the real estate it now owns in now-valuable downtown DC. GSA does this through complicated land-swap transactions, like proposing to pay for DOL’s new headquarters by trading away DOL’s existing three-block headquarters building at Constitution and 3rd St. NW.

In theory, it should be cheaper and easier for GSA to just build new office buildings itself. In practice, though, they’ve been trying to do so for the Department of Homeland Security at St. Elizabeth’s West — a process that Congressional underfunding has turned into a fiasco.

Parking craters will slowly go away on their own

In the long run, new parking craters will probably rarely emerge in the DC area. Real estate markets have shifted in recent years: offices and parking are less valuable, and residential has become much more valuable. This has helped to fill many smaller parking craters, since developers have dropped plans for future offices and built apartments instead.

Even when developers do have vacant sites awaiting development, the city’s growing residential population means that there are other revenue-generating options besides parking. “Previtalizing” a site can involve bringing festivals, markets, or temporary retail to a vacant lot, like The Fairgrounds, NoMa Junction @ Storey Park, and the nearby Wunder Garten. This is especially useful if the developer wants to eventually make the site into a retail destination.

Broader trends in the office market will also diminish the demand for parking craters, by reducing the premium that big offices command over other property types. Demand for offices in general is sliding. Some large organizations are moving away from having consolidated headquarters, and are shifting towards more but smaller workplaces with denser and more flexible work arrangements.

Unlike the boom years of office construction, there’s now plenty of existing office space to go around. Since 1980, 295 million square feet of office buildings were built within metro DC, enough to move every single office in metro Boston and Philadelphia here. While some excess office space can be redeveloped into other uses, other old office buildings — and their accessory parking lots — could be renovated into the offices of the future.

A version of this appeared in Greater Greater Washington.